The Settlement of Tatars in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

After Tatars and Mongols conquered some European lands in the 13th century, “Tatars” became a universal term to name the peoples belonging to the Golden Horde and different khanates. Lithuanian Tatars also bear the same name although ethnically they are Mongols, Kipchaks and Bashkirs. Historical sources feature a few scattered references to Tatars living in Lithuania in the early 14th century. Historian Albert Wijuk Kojalowicz writes, for instance, that Tatars served as the avant-garde of Grand Duke Gediminas’ troops, while the Franciscan monk Lukasz Wadinga describes in his Annales (1324) Scythians who spoke an Asian tongue and settled down in Lithuania after arriving there from lands run by one of khans. But both the historical truth and the versions of a legend explaining the settlement of Tatars in the GDL link the emergence of this Muslim community in the GDL with the late 14th century. Wars between the GDL and the Golden Horde, which took place at about that time, as well as the break-up of the Golden Horde and internal turmoil throughout that country were the key factors that encouraged Tatar migration to the GDL.

Were Tatars Vytautas’ allies or war booty?

The year 1397, the traditional date in the legend about the arrival of Tatars in the GDL, is related to the first Tatar settlement by the River Vokė. Established by the Great Duke Vytautas, it marks the beginning of the Tatar history in Lithuania. According to the legend, Vytautas – Vatat Bij, the king who crushes his enemies – brought Tatars and their families to the location by the River Vokė after the wars with the Golden Horde. He settled the Tatars down and gave them several plots of land in return for their faithful military service.

Polish chronicler Jan Długosz wrote down the story 83 years after the legendary settlement of Tatars in Lithuania adding more emotions and negative colours: “(Vytautas) Brought many thousand barbarians (Tatars – J. Š.-V.) with their wives, children and cattle herds to Lithuania as booty. To mark the victory, he gave some of them to King Władysław, Polish prelates and nobles leaving some for himself. The Tatars who settled down in Poland retracted from the errors of paganism, adopted Christian faith and grew into one nation with Poles through bilateral marital bonds. Others, who settled down in Lithuania, remained tied to their salacious faith of Mahomet. Brought by Duke Vytautas to one end of Lithuania, they still live there adhering to their customs and nurturing their impious religion.”

One should not be surprised by a somewhat insulting tone Długosz uses, because he a devout Catholic writing about the emergence of the non-Christian community in the GDL, the country that officially adopted Christianity just a decade ago. Długosz’s remark regarding Tatars brought in as war booty has sparked plenty of discussions among Tatars whose authors have offered their own interpretations correcting Długosz’s theory in their works on the history of the Tatar community published in the 20th century. The authors deny the fact of “bringing in” Tatars to the GDL while providing arguments that support the voluntary arrival of Tatars and their military involvement. Taking into account the sophisticated internal structure of the Tatar community and diverse social positions of the members of that community, researchers started to believe that at least part of Tatars came voluntarily and later received lands from the grand duke for their military service. They fought side by side with warriors from the GDL, while the other part of Tatars might well have been brought to the GDL as prisoners of war. They later became craftsmen and gardeners who lived in cities and their suburbs forming an absolutely unprivileged part of the society.

The fact that Tatars have preserved their religion and culture is yet another argument supporting the view that they were not prisoners of war, because if they were, they would have been assimilated by force.

The guardians of cities of the GDL

Tatars are obviously more pleased with the narrative which presents their arrival in Lithuania in glorious manner. It becomes clear reading Risaleh tarari Leh, the letter written by an anonymous Tatar, and noting the things he emphasises. The letter refers to Tatars who have responded to the call for military support by local rulers and who enjoyed the bounty of monarch’s grace and were allowed to stay in Vytautas’ courts after the victorious campaigns. This seemingly Tatar narrative features a number of factual and chronological errors, but researchers could analyse it more deeply anyway. However, the letter which has been long considered an important and unquestionably authentic source of history of Tatars in the GDL, has prompted some cautiousness among historians who now allege the document can be a fake. The key episode which explains the settlement of the Tatar community in Lithuania has been widely known and has been “borrowed” by Karaims who created a similar story about how they came to Lithuania.

Both legends and historical facts support the idea of first Tatars arriving in the GDL in the late 14th century, when the number of their settlements started to grow steadily. Tatars mostly occupied the lands given them by the grand dukes; therefore, it was easy to control the expansion of their community by turning their settlements into strategic objects.

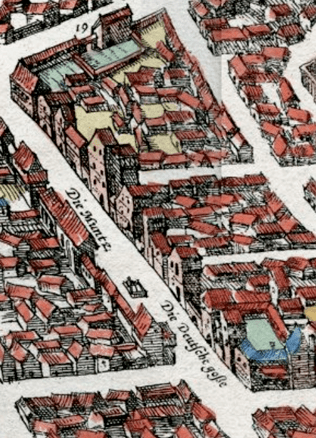

Tatar settlements and lands concentrated around political and administrative centres, such as Vilnius, Trakai, Navahrudak and Grodno, for quick mobilisation of the Tatar troops whenever situation compelled.

Tatars were kept farther away from the eastern borders of the GDL where the probability of conflicts with hordes hostile to the GDL was greater. It was later that the nobles made use of the scheme introduced by the state when they started forming their private squads and began offering Tatars land in exchange for military service by establishing Tatar settlements in their domains. The Radvila family have settled Tatars down next to Minsk, while the Ostrogski family have offered them lands in Slutsk and in Ostrog.

Jurgita Šiaučiūnaitė-Verbickienė