The diary of the King of Sweden and Vilnius

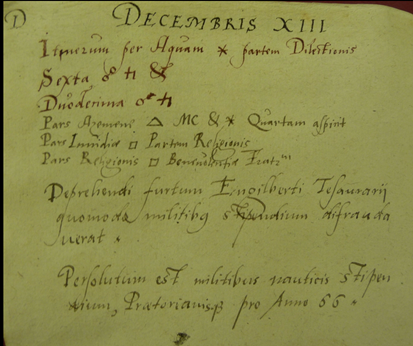

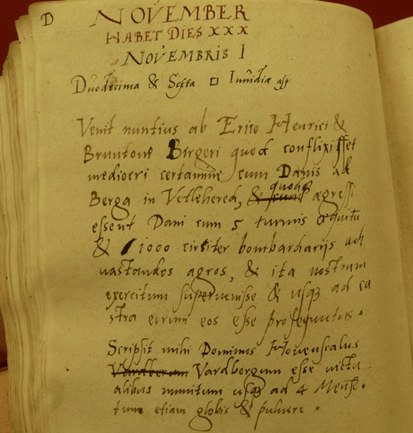

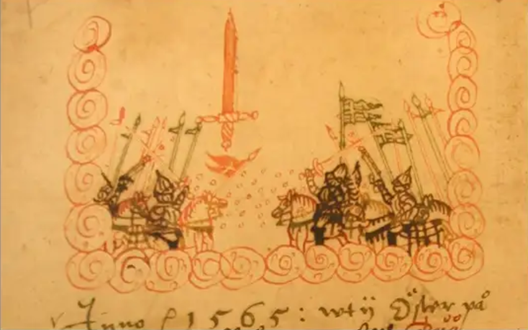

Notwithstanding his tragic fate and mental illness, King Eric XIV Vasa of Sweden (1533–1577) is remembered as one of the most cultivated monarchs in Renaissance Europe. Five centuries ago the texts on the interaction of the stars and planets were valued just as much as philosophers’ insights into the origin of the Earth and life, Eric XIV started writing an astrological diary in 1566. He began it in his royal court in Stockholm and continued in prison. He recorded his successes and failures, predicted perilous days, and did all that in Latin. Interestingly, he mentioned 28 September, 1568 among the bad days. On that day he was deposed.

The diary has not been published, yet the phrase habent sua fata libelli (books have their destiny) seems more than appropriate. Both the diary and its owner went through a number of ordeals and endured many travels. The diary’s history begins and ends in Sweden, but its route led through Vilnius.

King Eric and his ties to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

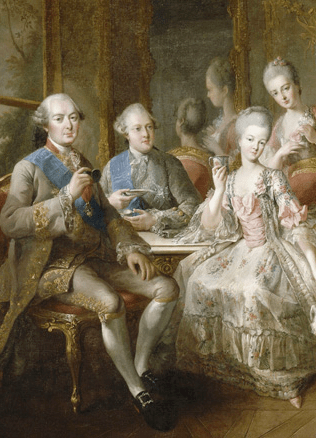

Eric XIV, crowned the King of Sweden in 1560, spoke four languages, was gifted at mathematics and military strategy, drew, played the lute, took interest in history and even keener one in astrology.

“

His eight-year rule was marked by almost ceaseless fighting, both against the opposition in Sweden and the enemies abroad, primarily Muscovy that aimed to dominate the Baltic Sea. Therefore, the Swedes wished that Eric married a Jagiellonian. He, however, nurtured an even more ambitious plan of becoming the husband of Queen Elisabeth I of England.

His eight-year rule was marked by almost ceaseless fighting, both against the opposition in Sweden and the enemies abroad, primarily Muscovy that aimed to dominate the Baltic Sea. Therefore, the Swedes wished that Eric married a Jagiellonian. He, however, nurtured an even more ambitious plan of becoming the husband of Queen Elisabeth I of England.

The Swedish magnates strongly contested this idea. The opposition included Eric’s half-brother John III Vasa who was married to Catherine Jagiellon. Terrified of conspiracy, Eric imprisoned them (1563) and proceeded to murder several members of the most influential family in Sweden. The killing prompted barely veiled speculations about Eric’s sanity that spread throughout the country, since he proceeded with murders after learning that his life is threatened by a blonde magnate from a horoscope. After the deed was done, Eric fled and resurfaced only three days later. But it was Eric XIV’s marriage to Karina Månsdotter that proved to be the last straw, because she was a daughter of a soldier and a peasant, a girl seventeen years his junior. Eric met Karina in an open-air market in Stockholm where she was selling nuts. He brought her to the royal palace and three years later, in July 1568 decided to take her as his lawful wife and the Queen of Sweden. In protest, Eric’s brothers did not attend neither the wedding nor the coronation. Supported by local aristocrats they rebelled, and in autumn of 1568 Eric was imprisoned.

Separated from wife and children

“

Brothers of the deposed King decided to separate him from his wife and children completely. He received no news of them up until his death by arsenic poisoning in 1577.

The diary of the deposed king tells its readers about much of this: the baptism of his first child, daughter Sigrid; the first son Gustav Eriksson (1568–1607) who was declared the legal heir to the Crown of Sweden when he was just six months old; the birth of two sons during his imprisonment, who lived for only four years and less than one respectively.

However, as it later turned out, this was not the worst episode of his life. Brothers of the deposed King decided to separate him from his wife and children completely. He received no news of them up until his death by arsenic poisoning in 1577.

Over the last four years of his life, Eric wrote a number of letters to his wife and drew several of her portraits, all retained in the diary.

The Swedish prince in Vilnius

“

Eventually the seven-year-old boy was sent to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth by the Queen of Sweden Catherine Jagiellon and spent two years in Vilnius. Not much is known about his life there, yet one fact beyond doubt is that he was a student of the Jesuit Academy from 1579 through 1581.

Eric XIV’s son Gustav Eriksson Vasa is among the most flamboyant and adventurous Swedes to have ever lived in Vilnius. One would hardly call his life very happy, though. He spent his entire childhood in captivity in Sweden and Finland where, together with his father, mother, brothers and a sister, he was held prisoner in various castles. From 1573 onwards he lived in the fortress of Turku with his mother and sister. In 1575, the King of Sweden John III decided to get rid of him in order to eliminate the likelihood of political conspiracy, yet John took an unusual decision for those times and exiled the prince instead of murdering him.

Eventually the seven-year-old boy was sent to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth by the Queen of Sweden Catherine Jagiellon and spent two years in Vilnius. Not much is known about his life there, yet one fact beyond doubt is that he was a student of the Jesuit Academy from 1579 through 1581.

Wandering around Europe and the fate of his father’s diary

The date of leaving Vilnius is unclear. We know that he took part in military raids against the Cossacks, visited a number of European courts, lived in Bohemia and several German principalities, and visited Italy. He was well-educated, had medical knowledge, took part in theatre performances, and spoke several languages.

“

It was her, Karina Månsdotter, who gave Gustav Eriksson his father Eric XIV’s diary during the brief encounter.

After returning to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth he met his half-cousin Sigismund III Vasa, who pledged him personal protection. During Sigismund’s coronation in 1587, he met his sister Sigrid after fourteen years of living apart.

Later he stayed in Torun and Gdansk, the Polish cities with strong Swedish diasporas. More years would pass before he would be allowed, in 1596, to meet his mother for the first time in twenty one years. The reunion, however short, would take place in Revel (present-day Tallinn).

It was her, Karina Månsdotter, who gave Gustav Eriksson his father Eric XIV’s diary during the brief encounter.

Muscovite hospitality turning to chains

Before long Gustav Eriksson found a new patron, the Tsar Boris Godunov. Gustav apparently was short of cash, because in 1599, just before the trip to Moscow, he pawned his father’s diary for money to a Vilnius-based Swedish merchant or perhaps an inn-keeper.

“

Not only Gustav Eriksson had to forget the tsar’s daughter, but he was soon taken hostage and prohibited from leaving Muscovy. The prince spent his last years in small provincial towns where alchemy was his virtually only retreat from the life of a prisoner.

As soon as Gustav Eriksson crossed the border, he was greeted by a large delegation, received several lavish dresses as presents, and was seated into a splendid carriage. After his arrival in Moscow, the prince was given a large house with a number of servants, and three rural districts as private property. Moreover, Tsar Godunov promised him his daughter’s hand as a political move aimed at granting the Muscovites direct access to the Baltic Sea.

The Tsar’s plan, however, fell through and once it did, his favours went with it. Not only Gustav Eriksson had to forget the tsar’s daughter, but he was soon taken hostage and prohibited from leaving Muscovy. The prince spent his last years in small provincial towns where alchemy was his virtually only retreat from the life of a prisoner.

His mother wanted her son back and was ready to pay the Muscovites a ransom, but she failed. In 1607 Gustav Ericsson died in Kashin, a provincial town about 200 kilometres north east of Moscow.

The diary kept on travelling

“

When in 1698 the Swedish state bought Ralamb’s entire collection of historical material, Eric XIV’s diary returned to its homeland. It is now kept at the Manuscript Department of Uppsala University Library.

Luckily, Eric XIV’s diary survived. In 1603 it was bought by Gregorius Laurentii Borastus (aka Greger Larsson, 1580–1654), then a Swedish student of the Jesuit Academy in Vilnius. From 1617 on he worked as a royal secretary for Sigismund III and other monarchs of the House of Vasa. Also known as a poet and historian, he wrote Historia Sueciae ab anno Christi 800 ad Ericum fere, a history of Sweden that offers the full text of Eric XIV’s diary.

The original account became part of the library of John II Casimir, the last of the Vasas. During his visit to Paris in the mid-17th century, the diary and many other historical documents disappeared, allegedly one of the court dwarfs sold them en masse. A couple of decades later, in 1673, Ake Claesson Ralamb (1651–1718) found the diary in a grocery shop in Paris. He was a Swedish nobleman and the author of his nation’s first encyclopaedia. When in 1698 the Swedish state bought Ralamb’s entire collection of historical material, Eric XIV’s diary returned to its homeland. It is now kept at the Manuscript Department of Uppsala University Library.

Raimonda Ragauskienė