Who Wore Coloured Clothes?

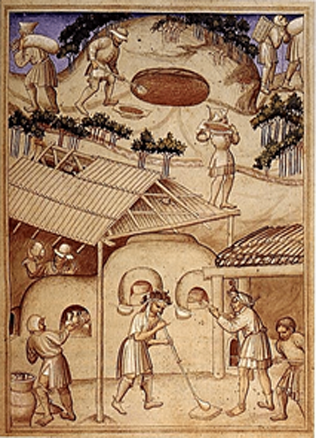

For a long time, Lithuanians wore clothes and footwear made of what they could get through agriculture and in forests. People were used to turning flax, sheep wool, furs and skins of wild animals, and bast fibres into simple, yet warm and practical clothes and footwear. Archaeologists have found plenty of spindles in female burial places which – and they have long had no doubts about that – indicate that spinning and weaving was vital for many families. For weaving, women usually chose linen or woollen yarns their thickness depending on the type of product. A vertical loom was a long-forgotten past in many Lithuanian families in the 13th century as horizontal devices dominated enabling to produce more sophisticated fabrics, such as kersey, three-yarn cloth, as well as checked and inwrought materials. Fabrics, clothing and headgear bore natural colours or were dyed. Blue of various shades was either the most widespread or the most popular colour. Woad (Isatis tinctoria), the natural source of blue dye, was and still is very rare in Lithuania, so people imported it. Red-coloured fabrics are infrequent too, because dyeing required imported colourants made of madder (Rubia tinctorum). Local plants were used to dye fabrics in yellow, brown and light brown, and black.

Judging by the needles and scissors occasionally found in burial places, both women and men were involved in garment making.

What buttonless clothing could people wear?

The attire consisted of linen underwear of varied thickness and several layers of outerwear, usually woollen. Women wore underclothes they had to slip on over the head, several shirts made of thinner fabric over them, and colourful skirts. Motley skirts were in fact several separate pieces of fabric worn one on top of the other, waist belted.

Alternatively, skirts could be worn like togas: a woman would wrap her waist with one-piece fabric before passing the loose end over her shoulder and pinning the edges together with a brooch.

Women usually wore a colourful wide apron on top of the skirt. To cover themselves, they had wide and warm shawls made of wool, fur and, occasionally, linen. They used various bands and belts, pins and brooches to keep their attire in place. Buttons came into fashion in the 14th century. Women often carried knives and leather pouch-shaped purses for keeping needles, threads and other small items. Men wore shirts and warmer jumpers, and their trousers were more sophisticated pieces of clothing compared to skirts. Long and tight trousers usually featured an added waist. Men belted their trousers using a piece of twine or belt; they also wrapped pieces of fabric around their shanks. Some men wore knee length trousers in summer. For colder weather, men had long woollen jackets worn under a jermiak made of thick kersey. Overcoats of different length were probably popular too, because people in neighbouring countries wore them. Men used the same items to belt and pin their clothing as women. Men of higher social rankings sported black leather belts – rare pieces of attire at the time. Much more often men wore girdles or shoulder belts – leather straps passing over both shoulders to hold shirts, underwear, a sword or a basket. Men’s clothing was pocketless, so they carried pouch-shaped purses too.

Clothing according to the owner

In winter, people wore warm overcoats made of lambskin or furs of wild animals. The overcoats of the ordinary people were incomparable to those worn by dukes and aristocrats in terms of materials, trimming and luxury. For instance, Vytautas, the Great Duke of Lithuania, would receive or give as presents overcoats of short-haired sable and ermine. People usually wore them fur inside, while on the outside they often featured applications of silk and other expensive fabrics or were embroidered with precious stones and golden threads, or dyed red. Sometimes fur overcoats had sleeves, sometimes they were used as surcoats. The luxury overcoats were different from the ordinary ones, usually made of any types of furs.

Headgear was an inseparable part of human dignity and life which, according to pagans, concentrates inside the head; headgear was a symbol and a sign of social status.

People were used to covering their heads at all seasons: men wore felt or fur caps, women preferred small caps, shawls and veils. Headbands were practical adornments because they helped to hold caps and shawls in place. Depending on the season, people wore leather boots, shoes, knee-boots, naginės (simple plain-sole footwear made of animal skin) or bast-shoes. In summer, many ordinary people were barefoot. Both women and men wrapped their shanks and feet with puttees. There is no historical data regarding knitting in the 13th– and 14th-century Lithuania. However, some people could sport knitwear, probably imported from Scandinavia, as the popularity of Scandinavian finger gloves along the merchant route between Daugava and Dnieper in the 13th century suggests. Lithuanians mot probably knew felt, a material popular with Tatars and other steppe nomads.

Baize and silk warm up body and soul

Clothing and abundant adornments carried out sacral and social functions. In the eyes of the Christian neighbours, that was a manifestation of paganism. Over the time, only the privileged classes continued wearing colourful clothes, adornments and other frills.

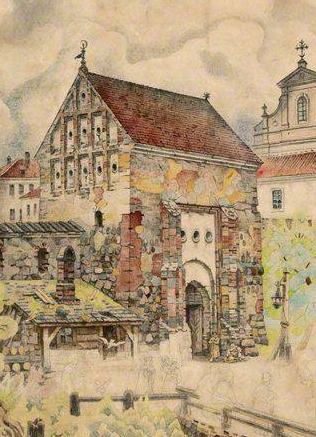

The Lithuanian aristocracy, the ruling family and dynasty in the first place, wore splendid clothes and expensive adornments either made by foreign tailors or imported – significant elements emphasising their social, political and military might as well as their exclusive status in the society. Military leaders, grand duke’s courtiers, loyal nobility (barons and satraps) all wore vividly colourful clothes made of exclusive materials in terms of their quality (such as baize), rarity (silk) and novelty (velour and velvet). According to historical sources, Prussians demanded that Poles give them horses and colourful clothing as presents, while the leadership of the German Order used overcoats and other items to smoothen hostile pagan hearts of the elite Samogitians who eventually turned against the baptism of Gediminas in 1324. The 14th-century stamps from bolts of exclusive fabrics unearthed in the Lower Castle in Vilnius, as well as in Kernavė and Trakai, indicate that merchants would bring expensive materials from Riga and from countries in the East and the West, but only the highest nobility could afford them.

Exclusive fabrics and clothes served as fine presents that grand dukes of Lithuania would receive from foreign guests and envoys of foreign rulers.

The royal attire

Western clothing fashions reached the court of the Gediminids in the first half of the 14th century. A goldsmith from Riga supplied the Grand Duke Gediminas with adornments. Travelling tailors from Riga probably made him some clothing. People gradually became used to adjusting their attire to the requirements of the estate-related daily activity, representation and ceremonies. In the second half of the 14th century, ducal seals feature images of rulers sporting knightly clothing. The description of the Gediminas’ seal attached to one of the letters he had sent to the West in 1323 speaks of the representative posture of the king: seated in his throne, he holds a sceptre and a crown in his hands. Although there is no description of his attire, presumably he wore something that fitted the ruler of the 14th century: a long shirt (a tunic) with sleeves and an overcoat. Vytautas wears this kind of clothes on his personal seal, his overcoat featuring a fur (ermine?) pelerine. The colours of the fabrics of the representative attire of the Gediminid dynasty are traditional in the context of the European courts: black, red, purple, and yellow (golden).

After the Christianisation of the country, in 1387, ordinary people tended to refrain from adornments, their clothes becoming ever more simple and the palette of colours reducing to white, grey and brown. Wearing colourful clothing became an unwritten privilege of the nobility.

Artūras Dubonis