The first critic of Lithuanian spiritual and public life Abraomas Kulvietis: conscience against Epicureanism

Do You Know?

Abraoamas Kulvietis (around 1510/1512–1545 06 06) is the first Lithuanian to have attained the ideals of Rennaissance humanistic education, forerunner of Lithuanian religious thought, a critic of Catholic church failures, founder of Evangelism (Protestantism) ideas, inspired by Reformation, in Lithuania.

Comprehensive studies in the best universities of that time

The Kulvietis family is related to the nobleman Ginvila, the name of the family stems from the Kulva manor, where the family had their land holdings (the present-day Jonava district). The only confirmation of Abraomas’s origin from the Ginvila family is found in the protocol of Kulvietis’ doctoral thesis, defended at the University of Siena (1540). In the protocol, Kulvietis is recorded as Ginvilonis as well: Abraoamas Kulvietis Ginvilionis, a lithuanian (lot. Abramus Culvensis Gynvilonis litevanus). On 14 September 1529 Kulvietis was awarded a Bachelor’s degree in Krakow university. However, he was not yet content with the studies, and took a long road in pursuit of knowledge in the universities of Western Europe.

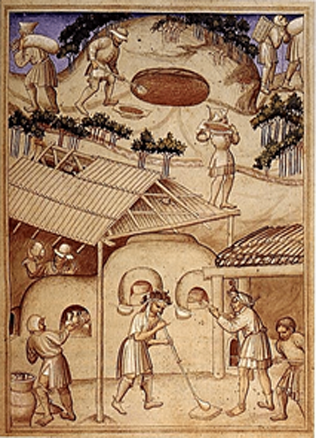

In 1533, Kulvietis enrolled the University of Leuven in the Netherlands and was the first Lithuanian to have studied at the Collegium Trilingue in Leuven, founded by Erasmus of Rotterdam.

He mastered Greek and Hebrew and formed a part of his humanistic library. In the spring of 1536 Kulvietis left for Germany to study in Leipzig university. In 1537 he entered the University of Wittenberg, the first Lutheran university in Europe. In Germany, Kulvietis communicated with Philipp Melanchthon, studied ancient philosophy, learned the German language and got acquainted with the ideas of Protestantism.

The protestant spirit of Abraomas Kulvietis matures in Italy

About 1538, Kulvietis left for Italy, visited Rome, later studied law in the university of Siena.

On 28–29 November, 1540 Abraomas Kulvietis defended his doctoral thesis in utroque iure in the University of Siena and became the first Lithuanian doctor of utriusque iuris.

The surviving protocol of doctoral thesis defence specifies the title of Abraomas Kulvietis canon law thesis as Clericus nec comam nec barbam nutriat, whereas the title of his civil law thesis was causa de testamento militis. The city of Siena, where Abraomas Kulvietis studied law, was the place of residence of many distinguished persons of those times. Among them was Bernardino Ochino (1487–1564), the vicar-general of the Order of Friars Minor Capuchin. Actively involved in his activities as vicar-general and an ardent proponent of this faith, Bernardino Ochino was soon (from 1542) to become a prominent figure in Italian Protestantism. Bernardino Ochino exercised crucial influence over Abraomas Kulvietis world-outlooks and his determination to publicly criticize the Church. Charged by the Inquisition with heresy, Bernardino Ochino fled to Geneva. In the autumn of 1542 Bernardino Ochino sent an open letter Epistola di Bernardino Ochino alli molto magnifici signori, li signori di Balìa della città di Siena, regarded as the first protestant confession of faith in Italy. The aforementioned letter and Bernardino Ochino’s unfailing courage to advocate “undisguised truth” influenced Kulvietis’ determination as well.

Humanistic activities in Vilnius

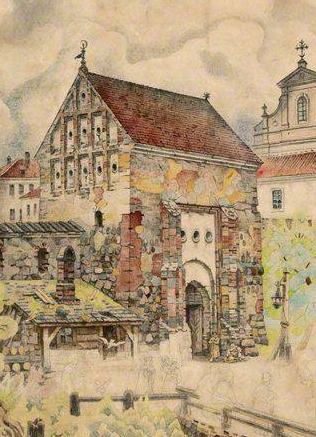

At the beginning of 1541, Abraomas Kulvietis returned to Lithuania as a doctor of both laws, determined to serve his country and launch active reforms in civic and religious life. Having introduced himself to Bona Sforza, the Queen of Poland and Grand Duchess of Lithuania, an Italian by birth, residing in the Palace of the Lower Castle, Abraomas Kulvietis won the Queen’s favour. There were few outstanding personalities contributing to the development of cultural and religious life of the country, in the court of a well-educated Sforza. Not surprisingly, she was positively impressed by the first Lithuanian lawyer and an erudite, to boot. The Queen’s support made it possible for Abraomas Kulvietis to open the first Lithuanian secular grammar-school in the spring of 1541. Classical languages and other humanistic subjects were taught at the school, which is thought to have imitated the model of Leuven’s Collegium Trilingue. In May of 1542, upon the initiative of the Bishop of Vilnius Paweł Holszański, the decree by Sigismund the Old was issued, on the basis of which Abraomas Kulvietis, pronounced “a rebel causing danger to the state,” was summoned before ecclesiastic court on allegations of criticizing and breaking away from the Church. Secular magistrates were obligated to bring him to court by force. Absconding from court would mean immediate deprivation of Abraomas Kulvietis nobility and citizen rights. This is the first decree in Lithuanian history, against an innocent person, who dared to publicly criticize the Church.

Threat of the stake forces the illustrious humanist to leave homeland

Bona Sforza warned Abraomas Kulvietis about a threat to be burnt to death at the stake, therefore by the time the decree was issued, he had fled to Königsberg. Duke Albert gave him shelter and entrusted him with all the work needed to establish a university. After the University of Konigsberg was founded in 1544, Abraomas Kulvietis was awarded professorial chair and worked at the University as professor of Greek.

At the beginning of 1543, Abraomas Kulvietis drafted the first text of Lithuanian Reformation in Konigsberg, the so-called Confessio fidei, which was written as a public letter to Queen Bona Sforza. In the letter, Abraomas Kulvietis emphasized the example of legal absurdity. He also stated that by raising charges against him, the Church becomes the judge in its own case. Abraomas Kulvietis requested the Queen to undertake the mission of an impartial judge, to intervene in the proceedings and determine whether he, committed to work for the sake of his motherland, could really be found guilty as a heretic, worthy of eternal exile.

Abraomas Kulvietis also stressed that he, the Lithuanian who had achieved the highest level of education in Western universities, had been doomed to be burnt at the stake not by the persons who were committed to serve the State and the genuine Church but by Epicureanists who were hiding behind the former, those who believed pleasure and well-being to be the sole intrinsic good and worshipped “their belly as God.”

Renew, not to destroy

Do You Know?

Opposing civic indifference, selfish hypocrisy and obsessive concern with one’s well-being, Abraomas Kulvietis raises and highlights the category of conscientia for the first time in the history of Lithuanian consciousness as the most important principle of professing religious truth and leading ethical life. This principle is enshrined in the New Testament.

In the part of the text which describes doctrinal truths, just a few ideas characteristic of early European Protestantism are highlighted, the ideas which Abraomas Kulvietis desired to be implemented by the Church through reforms, without splitting it. Abraomas Kulvietis also swore allegiance to the profession of Apostolic faith, and therefore regards himself as a member of the Church. He points out the idea of the gift of salvation not for merits or good deeds but by Grace alone, advocated by St. Paul, as an obvious religious truth of the Bible, ignored by the Church. On the basis of examples from early Christian Church, Abraomas Kulvietis raised requirements for the provision of two forms of the Holy Eucharist, recognition of two evangelical Sacraments and priests’ right to marry. He also called for prayers to worship God and to renounce prayers to the saints and the Virgin Mary.

Literature: Dainora Pociūtė (ed.), Abraomas Kulvietis: pirmasis Lietuvos Reformacijos paminklas /The First Recorded Text of the Lithuanian Reformation. Abraomo Kulviečio Confessio fidei ir Johanno Hoppijaus Oratio funebris (1547) / Confessio fidei by Abraomas Kulvietis and Oratio funebris by Johann Hoppe (1547). Studija, faksimilė, komentuotas leidimas, vertimas į lietuvių kalbą / A Study, Facsimile, a New Edition with Commentaries and Translation into Lithuanian, Vilnius: Lietuvių literatūros ir tautosakos instituto leidykla, 2011.

Dainora Pociūtė