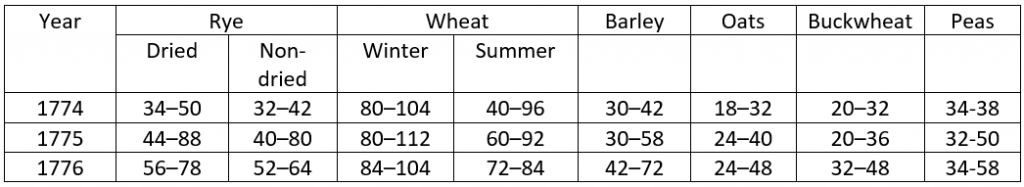

Prices of cereals in Vilnius in the second half of the 18th century

Many discussions are held about to what region of Europe (Central, East, Middle East) the Grand Duchy of Lithuania belonged. Most often political and cultural criteria are taken as a basis. Having in mind its constant existence at the intersection of the Western and Eastern worlds, and a diversity this position entails, sometimes western or eastern character of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania is postulated too hastily. According to Sigitas Narbutas, there are reasons to disregard the binary model and focus on the polynomial model of culture and writing.

Do You Know?

In the 18th century grain prices in the largest cities of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth were higher than those in Western Europe. Second-hand dealers who were unsuccessfully fought against had a great influence on that.

Social and economic matters could help to make clear to what European countries the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was closer: what the way of life of the larger part of society was or what standard of living of separate social groups was. Naturally the question of prices arises. Their changes and inflation reflect the economic development, and their comparison with the incomes of separate social groups reveals the purchasing power and the standard of living of the inhabitants. Most probable, without these data it is actually impossible to give an answer to the question of what place the Grand Duchy of Lithuania took in Europe.

Through the efforts of Franciszek Bujak school prices in several largest cities – Lvov, Lublin, Krakow, Gdansk and Warsaw were studied in pre-war Polish historiography. Unfortunately, Vilnius, one of the largest economic centres of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, was not included in that group. And prices differed in different places; they were determined by a comparatively large number of local markets and their small territories.

Fields that fed the country

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was an agricultural country and its production formed the basis for the sustenance of the population.

In the second half of the 18th century, proportions of three main cereal crops was as follows: rye accounted for 48 per cent, oats constituted 35. 2 per cent and barley stood at 16.8 per cent. (Mečislovas Jučas’ calculations based on the data from 25 estates). In 1765, the cereal crops in the wards of Upytė district were distributed as follows: rye – 37.9 per cent, oats – 34,3 per cent, barley – 22.4 per cent, wheat – 1.9 per cent, flax – 1.8 per cent, peas – 1.6 per cent, buckwheat – 0.1 per cent. The researchers do not agree on the size of the yields in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Some researchers say that the yield was 3-4 grain, others say that there were 5-6 and more. This was determined by quality: there were places where 8-10 grain was obtained, and when the year was fertile, the yield reached as much as 12-14. These figures are, most probably, exceptions. Especially small yields were in East Lithuania, in the former economic sphere of interest of Vilnius. Depending on the year the yield could differ significantly on the same farm. For example, in 1773-1785, the rye yield ranged from 3.4 to 7.7, the wheat yield – from 4.3 to 8, that of barley – from 2.4 to 6.0 and the yield of oats – from 1.7 to 5.9 on the well-managed estates of Nieborów near Łowicz (Poland).

At the end of the 18th century, 35 per cent of the people who lived in the cities and small towns were engaged in agriculture (not all of them grew cereal crops necessary for food), others were dependant on the products brought to the markets to be sold.

Family expenditure in the 18th century

Polish researchers state that in the second half of the 18th century there were about 350 kg of cereal crops (rye, wheat, barley, oats) per head. A part of this amount was sold abroad, another part was used for fodder or alcohol production; hence, about 150 kg of cereal products per head was used for annual consumption. A large part of the population had to supplement their diet with peas, cabbage and other products. The nobility could “play” with goods. For example, at the fancy dress ball that was held in Vilnius on 10 October 1773, a shop where “the Jews” presented ladies with various goods of high quality and expensive feminine products was staged.

Providing themselves with food, clothes and a dwelling in the conditions of colder climate was a matter of life or death for a large part of society.

Do You Know?

Living costs of separate families are an important issue. At first Fr. Bujak and his pupils thought that in the 16th-18th centuries, 65 per cent was spent on food, 18 per cent was spent on clothes, 12 per cent went to maintain a dwelling, 5 per cent was paid to heating and lighting. Stanisław Arnold criticised this view, he indicated that it was important to use typical data of a specific group in a specific epoch. For example, in 1723–1724, a merchant from Warsaw spent 69 per cent on food, 6 per cent on clothes, 9.5 per cent on a dwelling, 3.5 per cent on heating and lighting, and other expenditure (hygiene, servants, the church, etc,) accounted for 12 per cent. However, the budget even of such a person is not representative (by the way, this rich merchant was taken to court as “a drunkard and a swindler”). Unfortunately, hardly any data, which could help reconstruct the budgets of craftsmen, merchants, etc., have survived.

Both bad roads and rains made the prices rise

Though in 1785 the decree of Stanisław August Poniatowski was published in which the officials were instructed to announce the prices of goods, there are very few sources about the prices. The periodicals of that time are an important source, which throws light on the history of prices.

Prices of goods in the markets of the towns were indicated at the end of the newspapers or in their supplements.

The press of the town of Vilnius of the second half of the 18th century also contained this kind of data. In 1788, the Police Department instructed the cities and small towns to provide the editorial board of the publication Dziennik Handlowy issued in Warsaw with the annual prices of grain, which in 1786-1793 publicised many prices of different goods in the large cities of Poland and Lithuania (in Vilnius, Kaunas).

Investigations into the prices in different places are of significance because due to the weather and logistics problems the prices of the same products differed even in the places that were close to one another. The Polish historian Tadeusz Korzona notes that grain prices in 1766 in different places of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth could differ by as many as 9-16 times. Grain prices in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania were higher because of smaller yields and more expensive production.

Prices fluctuated in the same place. For example, in Warsaw prices of wheat could sore up to two times, and in Vilnius they increased almost up to 5 times. He supposed that this had been determined by poor crops. For example, the year 1785 was infertile. In the winter of 1787 wheat and rye increased in price up to 120 and 90 gold roubles for a barrel, respectively. In the spring of 1788, they did not go down much. Roads also had an impact on the market prices in Vilnius. Newspapers often wrote that prices went up because products could not be delivered, or too small quantities of them were delivered because of wet roads: on 21 October 1787 the following was written: “grain prices fall insignificantly due to poor delivery.” It is sometimes noted that despite large deliveries the prices did not fall all the same: on 23 September 1787, it was written that “despite yesterday’s large deliveries prices did not decrease at all, perhaps, they will go down in some time.” Sometimes it is noticed that some kinds of goods were not delivered at all. Poor crops caused by rains also had an effect on the prices: on 10 September 1785, it was written that “continual rains prevent the farmers from harvesting therefore prices of all grain and hey are constantly increasing in the market.”

One of the most “expensive” states in Europe

Prices of agricultural produce (rye, wheat, oats, barley, buckwheat, peas) constantly fluctuated: after harvesting in July and August, usually the lowest prices stabilised, then they gradually went up until they reached the maximum, finally, before harvesting the new yield prices increased even more. They directly influenced the prices of food products (cereals, flour and bread) made from cereal crops. Grain prices in the largest cities of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth were higher than those in Western Europe. Second-hand dealers had a great influence on that. Fight against them was unsuccessful. The data of Vilnius of the second half of the 18th century show that prices of the products made of cereal crops fluctuated in the market in the same way as they did in the largest cities of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

The price of wheat was the highest and the price of oats used for fodder was lowest.

Depending on the period, the prices could differ up to 50 per cent. They increased steadily. The future investigations should reveal what impact the prices had on the standard of living of the society of Vilnius and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Prices of rye, wheat, barley, oats, buckwheat and peas in Vilnius in 1774–1776 (gold roubles per Lithuanian /Vilnius barrel).

Source: Gazety Wileńskie, 1774–1776. Lithuanian / Vilnius barrel – 406, 5 litrų. Prices are indicated from min to max.

Literature: Gazety Wileńskie, 1774–1776; T. Korzon, Wewnętrzne dzieje Polski za Stanisława Augusta (1764–1794). Badania historyczne ze stanowiska ekonomicznego i administracyjnego, Kraków, 1883, vol. 2, p. 74–105; M. Jučas, Baudžiavos irimas Lietuvoje, Vilnius, 1972, p. 34–81.

Aivas Ragauskas