Of Daily Bread and Beetroot Soups, or What Did the Prince Povilas Alšėniškis eat in 1538–1539

In the 17th century, hot political discussions between Lithuanian and Poles would often end in spiteful jokes. Poles wished to sting Lithuanians who always opposed Poles and emphasised their independence. So, Poles used to spread jokes about insufficient religiousness and shallow Catholicism among Lithuanians, as well as about their dissolute women and batviniai, a soup with beetroot juice and leaves, that the whole Lithuania eats. Three Polish words – litwinie, swinie and botwinie meaning Lithuanians, pigs and the soup, were just perfect whenever someone wanted to rhyme a verse. Not surprisingly, the three words became almost inseparable. Leaving aside the origins of that “three-layer expletive”, we should notice that it provides some information on the Lithuanian culinary tradition. But how reliable is that information?

A slice of bread and flavourings in accordance to income

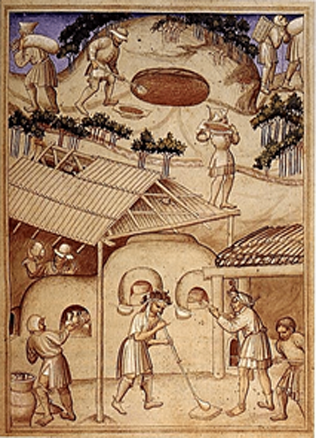

Historians can easily describe the characteristic features of food consumption traditions of a particular period. In the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period, people in Lithuania, just like in the rest of Europe, could not enjoy varied menus the good half of which was bread.

Since the turn of the 16th century, a loaf of rye bread has become a synonym of food.

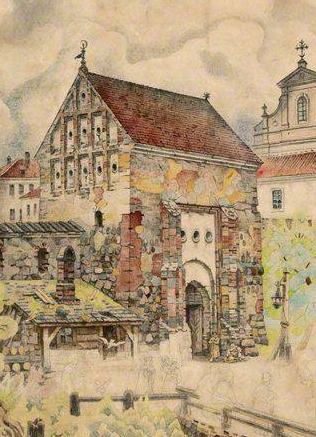

Obviously, people – even the poorest ones – tried to add other products to their daily rations, but the poorer the family, the less varied menu it could afford. We have some information dating back to the early 15th century about the foods that rulers of Lithuania would purchase in the market and consume. However, the share of locally produced meals on their tables was much lower than that of imported products, therefore, the historical sources are not able to say much about the regional tradition of food consumption in Lithuania. It was not before the first half of the 16th century that the first detached documents emerged reflecting the menus of the Lithuanian nobility too. Notebooks of expenses of Povilas Alšėniškis, the bishop of Vilnius, are one of such sources. They do not provide precise information on cooking and food recipes but refer to the main products the nobleman used daily and on special occasions. The three notebooks also shed light on the three types of food consumption by the bishop. The first one is that during travel (the trip from Vilnius to Pinsk in November 1538), the second one is that while living in his estate in Halshany (January 1539), the third one that while staying in Vilnius (lent of 1539).

In the preparation for the trip, the bishop’s cook visited several markets and pharmacies in Vilnius to buy food and spices: muscat (≈ 200 g), saffron (≈ 200 g), ginger (≈ 1 kg), cinnamon (≈ 400 g), cloves (≈ 400 g), almonds (≈ 600 g), rice (≈ 5 kg), raisins (≈ 1,2 kg), sugar (≈ 5 kg), caraway seeds (≈ 2 kg) and four large pieces of pork fat. Saffron and ginger were the most expensive products, each at 30 mites for 100 grams. The cook paid half mite for a loaf of bread of more than two kilograms. In other words, the same money could buy either 100 grams of saffron or 50 loafs of ordinary rye bread.

Travelling with a personal cook

In September, during his trip to and stay in Pinsk, the bishop apparently did not use the service of inn kitchens at all. His personal cook was in charge of preparing food for the bishop and he took all the main kitchen tools and utensils from Vilnius with him. Fish was the bishop’s most popular food during that trip. The cook would buy various fish – usually freshwater – almost every day. Once he bought salmon too. Part of it would end up on the bishop’s table almost immediately, but some of the fish – especially pike – was stored salted for later consumption. Vegetables, mostly turnips, were another almost daily purchase. Turnips remained the most important edible root vegetable on the tables of Lithuanian people up until the 19th century when potatoes became popular. In addition to that, the cook bought cucumbers several times and cabbages just once. The bishop’s kitchen also eggs and milk quite often. The notebook of expenses also says the cook bought wheat porridge and dried beetroot soup once. In regard with the latter, the document apparently refers to pickled beetroots. The list of purchases very rarely features meat. It was only once during the entire month that the cook bought two black grouse. It seems that the bishop did not eat much meat, salted or smoked, which had apparently been taken from his private estate rather than purchased during the trip.

The second notebook reflects the products the bishop bought while living at his manor in Holshany. Almost none of them! Just two times during the whole month did the bishop’s servants purchase salt and once they bought an eviscerated pig. The bishop’s storages would supply him with all vital food products. In this sense, he lived just like almost all nobility and peasants.

The bishop’s fast

Food expenses grew after the bishop moved to Vilnius.

During the 24 days he spent in Vilnius, the bishop’s servants would buy fresh products every day, including on Sundays. That was the period of lent and great fasting, which explains why the list of purchases never includes meat. However, the list features fresh bread, such as simple (apparently rye), white (wheat) and sift-flour, as well as bagels every day. The bishop’s cook would also often buy fresh fish to cook the main dishes of the day. The purchases included mixes of unsorted fish as well as fish of particular species, such as pikes, breams and roach. The bishop would eat fish several times a day. Herring was also popular on his table. It is likely that the cook would buy onions, mushrooms, oil and vinegar – which he did several times during that month – to use them in preparing herring. The notebook of expenses also brings the bishop’s traditional dinner table in front of us. The dinner menu was far from abundant as it included only dried fish, bread and beer. During the period of lent, the bishop had the soup of boiled beetroots six times on his table.

Why do Lithuanians like beetroot soups?

An attempt to take a closer look at the table of that particular nobleman leads to the conclusion that his menu, consisting of local products, was quite ordinary. The exclusivity of his menu lied in the fact that he ate fresh products cooked and otherwise prepared by a professional cook who used imported spices. Wine was probably the only imported product that the bishop consumed often, although not daily.

But what about batviniai, the beetroot soup? The name stems from botva, the Ruthenian word for leaves. The contemporary Lithuanian name for the soup, lapienė, has very much the same meaning – the leave soup. People used to cook beetroot leaves in summer when the old harvest had already been consumed and the new one still out in the fields. Cutting the leaves off does not harm beetroots themselves, but pickled beetroot leaves offer a food alternative until the new harvest ripens. The leaves, together with their sour juice, can be served as a hot or cold soup. The family name of the Samogitian noble who lived in the late 16th century, Šaltibarštis (cold beetroot soup), refers to the latter meal. In this sense, the joke about batviniai, the food of peasants, reveals old features of the regional cuisine that are still visible today.

Eugenijus Saviščevas