Magnates and their latifundias: appearance of large landownership

The right to a division of the spoils, tithes and gifts, which the nobility collected while in the surroundings of the Grand Duke or on the basis of their authority in the local communities, was the source of power and property of the nobility of Lithuania for a long time. Though there are hints about the land holdings given as a gift by the Ruler for service from the time of King Mindaugas, until the end of the 14th century this means of encouraging the subordinates was sooner an exceptional thing. There are data available about Duke Algirdas’ larger and more generous donations to influential noblemen Vaidila and Vaišviltas. However, these were individual cases of the Ruler’s graces. Some families of the nobility had more than one estate before the time of the reign of Władysław II Jagiełło and Vytautas, but landownership of the nobility became an essential social factor at the end of the 14th century only.

Do You Know?

The first “statistical’ document of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the military census of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania of 1528, reveals impressive scopes of landownership of the nobility families. The Kęsgailai family ran 12 288 properties (services), the Radziwiłł – 12 160, the only member of the Goštautai family, Albertas Goštautas – 7 456. Then followed the Dukes Olelkowicz and Ostrogski, Astikai, Glebavičiai, Zaberezinski, Kiszka, Chodkiewicz, Iljiničiai whose holdings included 2.5–7 thousand peasant farms.

The nobility encouragement programme

A wide land-ownership campaign was launched in the time of Vytautas’ reign – granting of lands with the peasant families to the nobility for their service. This campaign was in part encouraged by the Ruler’s traditional duty to remunerate his subordinates for their faithfulness and help. A decrease in military marches at the end of the 14th century made the Rulers look for new forms of donation. Inevitably they had to start using practice that was common for a long time in feudal Europe (known since the time of the reign of Charles Martel, the King of the Franks, at the beginning of the 8th century) – granting of lands. Since then land gradually became the criterion of richness. The success of the reign of one or another Duke, looking at it through the eyes of a nobleman, depended in part on the land-ownership policy pursued by him.

In 1434, the envoy of the Teutonic Order Hans Balga, in his letter to the Grand Master cited a secret conversation with the noblemen Andrius Sakaitis and Nemira’s son who compared Žygimantas Kęstutaitis and Švitrigaila Algirdaitis compiting for power from the viewpoint of their land-ownership policy: “Žygimantas used to give everybody who had patrimonial holdings a written confirmation, he also gave the same to those whom his brother [i.e., Vytautas] gave presents. In this way he earned people’s favours and showed his graces. But Švitrigaila did not behave in this way.”

Vytautas’ policy of giving lands for service was continued by those who succeeded him to the Duke’s throne.

At the beginning of the 15th century Casimir Jagiellon granted especially many lands and people to the nobility during his long years of reign, and entries in the documents of the Chancery of Lithuania of his time are even called “the book of gift giving”.

Poor control allowed the nobility to expand the holdings acquired even more by annexing the Ruler’s subordinates who lived in the neighbourhood. The last more significant stage of giving holdings as gifts took place at the beginning of the reign of Alexander Jagiellon. In the 16th century one can already see efforts (not too successful) of the Jagiellonian dynasty to put an end to a decrease in the Ruler’s domain.

The first “statistical” document of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the military census of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania of 1528, reveals impressive scopes of land-ownership of the nobility families. The Kęsgaila family governed 12 288 properties (services), the Radziwiłł – 12 160, the only member of the Goštautai family, Albertas Goštautas – 7 456. Then followed the Dukes Olelkowicz, and Ostrogski, Astikas, Hlebowicz, Zaberezinski, Kiszka, Chodkiewicz, Iljiničiai whose holdings included 2.5–7 thousand peasant farms.

A stripe to a stripe: the formation of holdings

In this way a large part of the country’s farming lands found themselves in the hands of the nobility. A temporary nature of giving lands as a gift was soon “forgotten”; attempts were made to concentrate these lands by way of buying, giving as gifts and exchanging in large holdings – latifundias and give them over, as patrimonial ones, to the heirs. In this way, complexes of the nobility’s holdings appeared (estates and small rural districts) which comprised entire peasant villages with several hundreds of peasant holdings: Manvydas family Žiupronys, Višniava, Mirkliškės, Goštautai family Geranainys and Trobos, Mantigirdaičiai family Yvija and Loskas, Radziwiłł’s Upninkai and Musninkai.

Though the nobility’s landownership further remained scattered, attempts to concentrate the lands (by buying, exchanging) in several territories are observed.

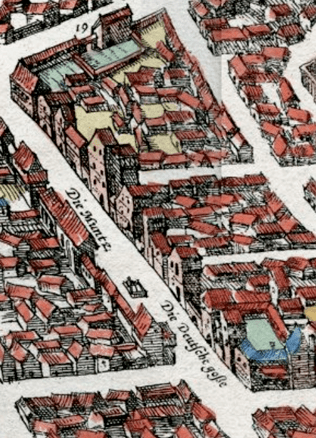

One of these territories was Ashmyany district where many noblemen had their old patrimonial holdings. Manvydai Žiupronys or Goštautai Geranainys are obvious cases of the expansion of patrimonial holdings. Another trend was to establish wide latifundias where “there was plenty of land” – in the regions being colonised. Podlachia was an especially favourite region – the forest wasteland that was on the border of Lithuania, Mazovia and the Teutonic Order for a long time and which during the peaceful period was started to be settled intensively. The Radziwiłł and the Goštautai acted there intensely from the 15th century (Goštautai Tikocin, Radziwiłł’s Goniądz and Rajgród). Other families (the Chodkiewicz’s Suprasl, Sapieha’s Koden, etc.) followed in their footsteps.

Each larger holding (estate) had its central farmstead (some of them could perform the functions of the nobility’s residences) around which outside buildings and buildings intended for the family that was not free were concentrated. Because of the requirements of the military service, as well as for reasons of representation, there were stud farms in some of the estate. From the beginning of the 16th century castles of the nobility began to be built in the centres of the most important holdings. Administration of the holdings was a complicated matter because one holding could be separated from another one by as many as several hundred kilometres. They were supervised by deputies. Both small local noblemen and specially hired newcomers were appointed deputies.

The Radziwiłł’s Biržai and Nyasvizh can serve as an example of appearance of a large holding. In the middle of the 15th century, Casimir Jagiellon signed over several peasant homesteads to Radziwiłł Ościkowicz. In the 16th century this was one of the largest family holdings whose significance was testified to by the titles of dukes acquired by the Radziwiłł – Dukes of Nyasvizh and Olyka, and Biržai and Dubingiai.

Rimvydas Petrauskas