Lithuanians’ Heaviest Loot, or How the Bronze Doors of the Płock Cathedral Ended Up in Novgorod

The growth and strengthening of the troops of the monarch was one of the most important signs of the formation of the Lithuanian state in the 13th century. The warriors and their commanders “fed” on predatory raids to foreign lands. Historical sources refer to Lithuanians as to warlike groups of men ready to raid and plunder neighbouring tribes but hardly consolidated in political sense.

Do You Know?

Livonian chronicler Henry of Latvia offers a lively description of the situation the tribes living along the River Daugava were in: “Livs and Latgalians were fodder and food for Lithuanians, just like sheep in wolf’s jaws.”

The authority of the Lithuanian king Mindaugas, that grew considerably in the 1250s, and the concentration of the Lithuanian military potential enabled Lithuanians to carry on simultaneous raids in several directions. The material goods and slaves captured during the raids to the “Latvian” lands along the River Daugava as well as to Rus and Masovia were important for Lithuanians, because the war booty enriched participants of the raids and increased their commanders’ social prestige. The Lithuanian expansion was an important factor that prompted some tribes, such as Livs and Latgalians, to accept easily the authority of the Livonian Brothers of the Sword and the Bishop of Riga, because they were able to protect them, at least partially, from the merciless Lithuanians who spoke similar language but would storm their lands routinely, like a natural disaster.

In the second half of the 13th century, Lithuanians discovered a new object for their raids and plundering – Masovia, the land at the eastern edge of the then little-known Poland. United Poland did not exist at that time, because the country was then split into several duchies their rulers fighting fiercely for power. The first documented raid in Poland took place in 1262, when Lithuanian troops devastated the Płock land and the ducal estate of Ujazdow, now part of Warsaw. In an ironic twist of history, the Embassy of the Republic of Lithuania in Poland is now on the Ujazdow Alley. In the 13th century, however, Warsaw was backwoods of Masovia rather than the capital city of Poland.

The riddle of unprecedented cruelty

The Chronicle of Greater Poland says that the Lithuanian warlord Švarnas invaded Ujazdow on the eve of St. John’s day and “beheaded the captured duke Siemowit himself and took his son Konrad with him to captivity.” Some sources add that Švarnas burned Siemowit’s body down. Historians maintain, apparently with good reason, that Lithuanians were lead by Mindaugas’ nephew Treniota rather than by Švarnas during that raid.

The contemporaries have singled out the violent killing of the Polish duke as an extraordinary act of the time, but its details, including the beheading and burning down, point to certain rituals performed by Lithuanians.

As such, the sacrifice of captives should not be considered an extraordinary deed among Lithuanian troops, because historical sources refer to a number of such cases following successful military raids in the 13th century. Beheading is a custom of ritual fragmentation of the body and a punishment for breaking the set order of life characteristic to the old tribes. It is unclear, however, why should one need to kill a duke. Should the military commander stay alive in the battle, he was usually taken captive even during the conflicts involving different societies, because the winning party expected to exchange the enemy’s commander for ransom. This is exactly what happened to Siemowit’s son Konrad, who was freed after several years in captivity. Another Siemowit, the captive duke of Dobrzyn, was apparently freed for ransom in 1296. This leads to the conclusion that the beheading of the duke of Masovia was caused by extraordinary circumstances unknown to us, which justified the violence against a duke.

A Lithuanian miracle of logistics

Lithuanians brought home a much heavier loot that time, though.

Around the same time, a massive door weighing several tons went missing in the Cathedral, Masovia’s main church.

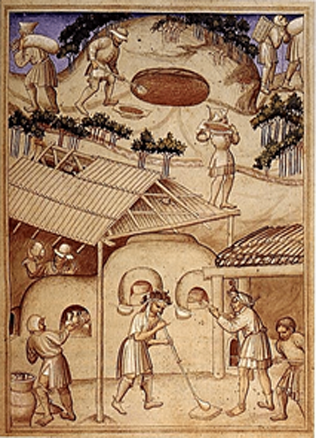

The bronze Roman-style doors of high artistic value were made back in the mid-12th century in Magdeburg, commissioned by Alexander, the then bishop of Płock. Much later the door emerged 1,000 kilometres northeast from Płock, in the Cathedral of St Sophia in Novgorod, the city in the Northern Rus. How, when and in what circumstances did the door arrive there? Unfortunately, the historical sources say nothing about the transportation. It is hard to believe, but the contemporaries have turned a blind eye on that episode, perhaps simply because they were not able to comprehend how that great treasure became theirs. Even in Soviet times, Russia denied the door was originally from Płock offering a theory instead that the door had been snatched from the Swedish town of Sigtuna a long time ago by Curonians who then allegedly were under Novgorod’s authority. The historians, however, have since provided plenty of arguments that proved irresistible and Russians had to come to terms with the “Polish” origins of the door. The Płock Cathedral has been featuring the replica of that door since 1982. But the question regarding the transportation remains unanswered. In the 20th century, Polish historians offered an assumption that the door had been moved by Lithuanians who devastated Masovia in 1262. Lithuanian writer Kazys Almenas later added some vivid arguments to the hypothesis. Indeed, why should not we stick to the notion that Lithuanians were behind all of that? In the 13th and 14th century, Lithuanians had virtually no “competitors” capable of performing that kind of plunder in Płock – and there is no doubt that was a plunder. Lithuanians apparently saw the door as a very valuable, though very heavy, booty which they eventually sold to other Christians, the Orthodox people from Novgorod. At the same time, this story may give some hints regarding the logistics of the Lithuanian troops, the matter that the historical sources of the time left in total oblivion otherwise. We can imagine artisans and merchants though who, hired by Lithuanian warriors, disassembled the heavy booty, then found the easiest way to transport it by land and across the rivers, and then put it together again.

Literature.: R. Petrauskas, Lietuviai anno Domini 1262: Kodėl buvo nukirsdintas Mazovijos valdovas Siemovitas?, in: Naujasis Židinys–Aidai, nr. 7, 2011, p. 442–447; K. Almenas, Katedros durų mįslė, in: ten pat, p. 448–460.

Rimvydas Petrauskas