Lithuanian Orthodox Metropolitanate (1316–1458)

The Metropolitanate of Kiev and its dioceses was a local Church organization, the beginnings of which are traced back to the baptism of Rus’ in 988. It was subordinate to the Patriarch of Constantinople. The area of Kiev Metropolitanate was the largest at that time. In the 14th, 15th and later centuries it became the richest Orthodox ecclesiastical province. During the times of the Kievan Rus’, most metropolitans were of Greek origin. From the second half of the 13th century, though, adherence to an unwritten rule was observed: upon the death of the Greek Metropolitan, a local Ruthenian was appointed as his successor, to be followed by yet another Greek, etc. According to the 14th century Byzantine historian Nicephorus Gregoras, such throne inheritance practice and the principle of supporting a united metropolis was a wise idea devised by ancestors, aimed at a successful maintenance of friendship between the Greek and Ruthenian nations. A long-term Kiev’s ecclesiastical subordination to Constantinople and the prevailing administration practice are important factors to be considered during the analysis of Lithuanian rulers’ actions in the sphere of Rus’ Orthodox Church activities. After Lithuanian dukes occupied Orthodox lands, they entered the world characterised by a certain order and rules, which the Lithuanian dukes were neither able nor willing to radically change.

Lithuanian challenge to Muscovy

Do You Know?

Lithuanian dukes had to adjust to existing conditions. In the late 13th century, after Metropolitan Maxim left Kiev, the centre of Rus’ ecclesiastical life was transferred to north-east Rus. Finally, in 1326, when Metropolitan Peter chose Muscovy as his residence and eternal resting place in 1326, the tradition of joint actions between Muscovy dukes and Rus’ metropolitans was established. Metropolitan’s residence in Muscovy raised the prestige of Muscovy dukes, regardless of the fact that during the period in question they were loyal to Tartar power in Rus territory. Coexistence of Orthodox church, Muscovy dukes and Tartars created a change-resistant system.

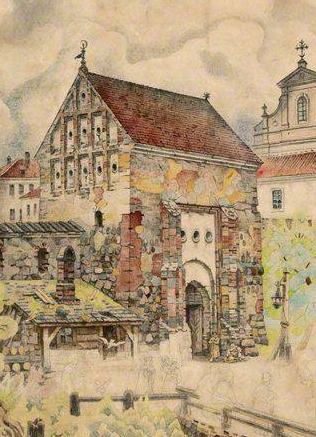

The first Lithuanian ruler attempting to change the autocratic position of the Metropolitan residing in north-eastern Rus’, was Gediminas. His diplomacy must have been the decisive factor in ordaining Theophilus as a separate “Lithuanian Metropolitan” in Constantinople in 1316. Navahrudak became capital of the Metropolitanate, with subordinate Polotsk and Turov dioceses. Theophilus did not limit himself to the activities in his sphere of competence. He travelled a lot all over Rus’ and increased the number of his supporters through gift donation. In fact, what he sought was power in the whole of Rus’ Metropolitanate rather than power within the boundaries of the Lithuanian state. Meanwhile, the Patriarch of Constantinople had realized that Orthodoxy would never become widespread among Lithuanians. Upon Theophilus’ death in 1330, he decided that pastoral care of Orthodox Christians could be delegated to Muscovy Metropolitan, and did not appoint Theophilus’ successor. Lithuanian Metropolitanate remained vacant. Similar things would happen in the future.

The country’s Metropolitanate, obtained as a result of enormous efforts, ceased to exist after the death of a Metropolitan.

Such institutional weakness of Lithuanian Orthodox Metropolitanate shows that the Patriarch of Constantinople agreed to ordain a separate Metropolitan for Lithuania only in exceptional circumstances, only to return to traditional order later on. Such order was more favourable to Muscovy.

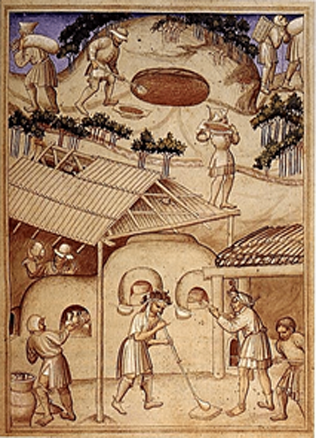

Surveying the lands of Rus’ through the gates of the Orthodox Church

The strongest attempts to have a Lithuanian Metropolitan can be traced back to Algirdas’ reign. A fight broke out over the succession to Metropolitan Theognostus in 1353. Upon his death, Muscovites did their best to send to Constantinople a representative of boyar family Alexei, closely connected to Muscovy dukes. Algirdas tried not to lag behind them and dispatched his candidate, the monk Roman born in Tver. Alexei fared better – after a trial period of one year he was appointed Metropolitan of Rus’. However, even in such circumstances Algirdas did not give up. He succeeded in convincing the newly enthroned Patriarch Callistus to ordain his nominee, the monk Roman, into Metropolitans as well (1354). The presence of two Metropolitans in Rus’, though, resulted in a huge turmoil of the Church, which subsided only upon Roman’s death (1361). This was a struggle for leadership in the whole Church of Rus’. Such aspirations declared by ecclesiastic candidates were advantageous both for Muscovy and Lithuanian dukes. Even though the Church of Rus’ was not subordinate to secular power, Muscovy and Lithuanian dukes used it in order to spread their political influence. This phenomenon was aptly described by Patriarch Nilus in 1380, in his memories about the battle waged between Algirdas and Alexei: “When other people tended to behave peacefully and maintain calm, this fire-worshipping Lithuanian Duke, determined to attack and devastate any state and subdue any town any time, much as he desired, failed to get a hold on the Great Rus’ and therefore found no peace. Instead, burning with hatred for the Metropolitan, he tried to harm the Metropolitan in all possible ways.”

Do You Know?

Algirdas sought to gain power in Rus’. Ordination of a separate Lithuanian Orthodox Metropolitan was important to him not as a factor serving to integrate GDL Orthodox Christians but as a political tool of power across the whole eastern Slavic area. In this respect, Algirdas’ political vision was oriented to the Rus’ Metropolitans’ spiritual sphere of power.

The union of the Orthodox Church and schism

Political pluralism, prevailing in the Rus’ lands in the 14th century, gradually promoted not merely the alienation of its separate parts but also strengthening of regional identity. This process was further developed both by Lithuanian rulers and Muscovites, who sought to exercise influence over the Metropolitanate. This became particularly obvious in 1375, after the ordination of Kievan Metropolitan Cyprian, the candidate proposed by Algirdas. For a long time (until 1390), Muscovites refused to recognize him and dubbed him “a Lithuanian.”

Within the GDL context, a preference for local Church interests became obvious in 1415, during a meeting of GDL Orthodox bishops in Navahrudak, when Gregory Tsamblak was chosen as their Metropolitan. The bishops renounced Muscovite Metropolitan Photius, having accused him of wrongdoing against local (GDL) Church. Actually, in 1420, Photius regained his spiritual power over GDL Orthodox Christians. This is sufficient proof that Lithuanian Orthodox Metropolitanate separation process was slow.

The breakthrough came only after the Florence Union between Catholics and Orthodox Christians was concluded in 1439.

In 1448, Muscovites elected John as their Metropolitan, regardless that Isidore was a canonically elected Metropolitan, the one who had signed an Act of Ecclesiastic Union. Only in 1458 a way out of the impasse was found, after Pope Pius II appointed Gregory the Bulgarian as successor to Isidore. All aspirations declared by both Muscovite and Kievan Metropolitans to gain power over “the whole Rus’” faded away. From then onwards, a Muscovite and Ruthenian churches started to exist. The latter went on upholding Kievan Rus’ traditions and maintaining contact with the Patriarch of Constantinople until 1685–1686, when the Kiev Metropolitanate became subordinated to the Patriarchy of Moscow.

Literature: M. Giedroyć, „The Ruthenian-Lithuanian Metropolitanate and Progress of Christianisation (1300–1458)“, Nuovi studi storici, 17, 1992, p. 315–342. S. C. Rowell, Lithuania Ascending: A Pagam Empire within East-Central Europe (Iš viduramžių ūkų kylanti Lietuva: Pagonių imperija Rytų ir Vidurio Europoje), 1295–1345, iš anglų k. vertė O. Alekna, Vilnius: Baltos lankos, 2001.

Darius Baronas