Jewellery Technologies in the 14th Century

In the 13th and 14th century, artisanship has reached a new qualitative level in the culture of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. In the earlier times, artisans usually worked only to satisfy the needs of the local community. In the historic Lithuania, artisans, already specialised, used to set up their homes next to ducal residences, while their production was expected to meet the requirements of the market and the nobility of the time. The latter processes are obvious in jewellery. Many former Slavic cities in ethnic Yotvingian lands, including Navahrudak, were incorporated into the GDL in the 13th century. Jewellers and goldsmiths in Navahrudak inherited ages-long artisanship traditions of Kiev Rus that had developed amid the cultures of Byzantium and Scandinavian Vikings. Therefore, Slavic artisans – who were familiar with a broad spectrum of complex technologies – have worked to satisfy the demands of the Lithuanian ducal court since the times of Mindaugas’ reign in the mid-13th century.

Baltic aesthetics and Slavic technologies

Archaeological research of artisan homes in Kernavė has yielded large amounts of data revealing specific aspects of jewellery of that time. Artisans’ main source of living was their craft, because archaeologists have not found neither agricultural tools nor sheds for cattle beside their homes. Every artisan was a specialist in certain area. One of the two artisans in Kernavė was a jeweller, while another was a bone carver. They used their living houses and workshops for several decades and sometimes rebuilt them at the same place. It was there that archaeologists have found many tools and pieces of metals, bones and horns. The findings indicate that specialised crafts and technological know-how was something that artisans would give over as a heritage to younger generations.

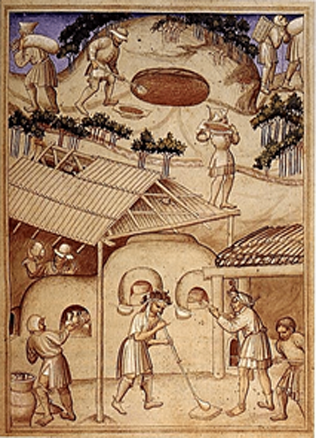

Baltic jewellery of the 14th century is astonishing in terms of the variety and complexity of technologies used to make these pieces of jewellery. In the prehistoric Baltic cultures, most jewellery was made simply by casting using stone or clay moulds. In the Viking epoch, more complex technologies were employed as artisans used various metals and solders to produce a single item.

A jeweller had to be both a skilful artisan and a creative chemist.

The level of the art of jewellery was high in the 14th century, judging by the hoards of adornments unearthed in Lithuania. The adornments combine archaic Baltic shapes and elaborate technologies adopted from Slavs and dating back to the Viking times.

Eight production techniques in a single brooch

To make a single horseshoe-shaped silver brooch found in the hoard of Stakliškės, a jeweller had to be proficient in at least eight production techniques. Using only his hands, he had to be able to strain at least several metres of silver wire of different diameters, including a very thin wire, less than one millimetre in diameter. Employing the techniques known to him alone, he then had to weave out a rim of the brooch using more than ten together-wound wires. He then had to rivet imposing heads of the brooch, themselves made by means of casting and resembling tiny horse heads. The decoration of the horse heads and the tenon of the brooch involved at least three other technologies: precious stone encrusting, weaving twine-like ornaments made of extremely fine wire and soldered to the body of the brooch (a filigree technique), and tiny silver fringes (a technique of granulation). The ends of the brooch rim are ornamented with tiny embossed triangles. The old master made everything, even the finest details of ornamentation, without contemporary electric tools and event without a simple magnifying glass, in daylight or in a room lit by a burning splinter.

Art, science and skill mixed in jewellery

The round plate-like Baltic brooches from the hoard of Stakliškės are decorated with soldered silver wires and another new technology, blacking. Black or brownish substance derived from sulphur and other chemical elements was used to fill up the recessed areas of the relief picture on the body of the brooch. This technology helps base metals shine out with more pronounced colours. The 14th-century rings from Kernavė decorated with fylfots also feature blacking, the technology that has no analogues yet among other urban material of that time. The rings that look quite solid are in fact hollow, made of fine silver plate using purpose-made matrixes. Artisans used matrixes to make identical products on a massive scale. Archaeologists have unearthed a number of silver gilded headband plates and their production matrixes in Kernavė. The findings point to the fact that the local jewellers were proficient enough to make these remarkable decorations. Most of the headband plates found in Kernavė were gilded. Gold amalgam the artisan used to gild his products was a chemical compound that included mercury. The skills and creativity of the artisans of that time are just astonishing. They had to import all the metals and most of the chemical elements from other countries.

A big part of jewellery discovered in Kernavė and in the Vilnius Old City stands out among other findings in urban areas because of their subtle shapes and the broad spectre of jewellery techniques employed. Therefore, the earliest cities of the GDL had their own individual school of jewellery influenced by the archaic Baltic concepts of plasticity of metal forms and new technologies brought in from neighbouring countries.

Gintautas Vėlius