Hunting: pastime of the court, means to do politics, and an economic necessity

At the turn of 1413 and 1414 the Knight Chillibert de Lannoy from Burgundy who visited Vytautas’ estate found the Ruler of Lithuania and his wife and their daughter who had come on a visit with their granddaughter in one of the castles near the Nemunas River. On that occasion the guest wrote in his travel notes the following: “The Duke has arrived in the place where he goes to in winter as usual to hunt in the surrounding forests. He stays there three weeks or a month without going to either of his estates or towns.” It was not hunting that surprised the experienced knight – hunting was the most favourite hobby of the nobility all over Europe, a peculiar kind of sports of the nobility of that time. What surprised him was a long time, which the Grand Duke spent far from his estates and day-to-day political activities. But hunting and day-to-day political activities were related, nonetheless.

Political success of hunting

In the Middle Ages, hunting was not only the way of spending time for the nobility but also the form of political communication and economic necessity. In the language of political symbols joint hunting meant a union – the best example of such an agreement is the Treaty of Dovydiškės, which Władysław II Jagiełło and the official of the Order concluded during hunting in the wasteland. Jagiełło and Vytautas sometimes used hunting seasons that lasted for months to discuss political issues. Special hunting estates (Germ. jagdhove) used to be prepared to serve such outings. For example, at the beginning of 1421, Jogaila and Vytautas received a large delegation of Hussites in the hunting estate in Varėna, which discussed an important political matter with the Rulers of Poland and Lithuania – the offer to accept the crown of the Czech Republic.

Joint annual hunting sprees of Jagiełło and Vytautas that began after Christmas became a strong part of their interrelations.

The cousins did not refuse this habit even in the winter of 1429–1430 though their relations became strained because of Vytautas’ decision to become crowned King of Lithuania. During joint hunting on the Polish and Lithuanian border at the end of 1409 Vytautas and Jagiełło most probably discussed the plan of their great invasion into the territory of the Order. It might be that during that hunting spree food was started to be stored for that march. Even when they reached a respectable age Jagiełło and Vytautas remained faithful to their passion. In April 1427, having recovered from a serious illness Vytautas announced joyfully to the Great Master that “they were already going hunting”. And during the last years of his life, despite worries about the coronation, Vytautas went hunting in the environs of Varėna. Though the main hunting season was winter months, the data of the sources show that he found opportunities to hunt during other seasons too.

Do You Know?

In 1408, the Grand Master of the Order presented Vytautas’ zoo with a lion. The following year, in return for that, Vytautas presented the Master with four live aurochs, as a clerk of the treasury of the Order noted.

The hunting areas stretched through the forests that formed the border with the Order therefore requests for permission to hunt in the woods of a foreign territory are constantly found in Vytautas’ letters to the Master. These special permits issued to the ruler of the neighbouring lands to hunt in his territory (“letters of hunting”) were an important aspect of the relations between Vytautas and Jagiełło and the Order. Their announcement testified to the desire to preserve and develop friendly relations therefore they can be assessed as a peculiar substitute of the joint hunting sprees (which Vytautas and Master usually did not organise).

Diplomatic “paths of beasts” in Europe

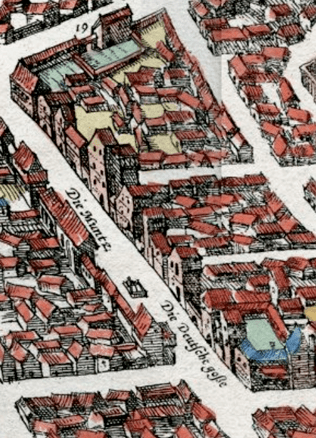

Main game of hunting went to the table of the Grand Duke and into the barrels. Venison formed an important element of food of the Ruler’s court. Some trophies found themselves in the Duke’s zoo, which was an inseparable part of the monarch’s court. The Grand Master had a good zoo, which provided the estates of the Rulers of other European countries with exotic animals. The above mentioned Guillebert de Lannoy saw Vytautas’ zoo in Trakai: “There is a fenced zoo in the town of Trakai. All kinds of wild animals and hunting animals, which reproduce in the forests, are kept there. For example, wild oxen called European bisons, also big horses called mules and others. The lion was an adornment of the zoo for some time, which was presented to Vytautas in 1408 by the Grand Master of the Order. The following year, in return for it, Vytautas presented the Master with four live aurochs, as the clerk of the Treasury of the Order noted. And in 1416, Jagiełło and Vytautas sent “a large beast”, as the Chronicler of the Council Ulrich of Richental called it, to Sigismund of Luxembourg, Holy Roman Emperor, to the most holy general synod of the Council of Constance. Thinking that the animal will not reach Sigismund’s court alive, it was, citing Ulrich of Richental, “salted within its own skin”. With pomp, in the presence of heralds, Sigismund sent on that giant from Constance to the King of England. Shooting of falcons was a special occasion. The Holy Roman Emperor Friedrich II wrote a book on shooting falcons in the 13th century.

Presenting gyrfalcons became even a diplomatic form in the long run. According to unwritten rules, the value and number of falcons being given as a gift reflected the rank of the person being presented with them and political relations of the parties taking part in the gift-giving act.

Mainly Russians who were supervised by the court’s falconer took care of the falcons in Vytautas’ court. Vytautas used to lend some specialists to other rulers too. Journeys of falcons and falconers reveal interrelations between the European courts. For example, in April 1409, the white falcon and other birds carried by Vytautas’ servants reached the estate of the Grand Master. The Master forwarded these gifts together with the servants through Danzig as a present to the Duke of Burgundy. The position of falconers known in the sources from the end of the 14th century testifies to the fact that falcon breeding was well-developed in Lithuania. Episodes from the life of falconers show that there might have been persons of noble descent among them too: falconer Isaya, during the time of Skirgaila’s reign, testified together with other noblemen on behalf of one Duke by signing a guarantee document, and his colleague Theodore Vesna was even entrusted by Jagiełło to govern Vitebsk.

All members of Jagiellon family were ardent hunters until Sigismund Augustus. When Casimir arrived in Lithuania from Poland, as the route of his trips shows, he spent more time in his favourite hunting grounds than in the meetings with the nobility. This hobby of the rulers acquired a cultural expression in the poem A Song about the Appearance, Savagery and Hunting of the Bison by Nicolaus Hussovianus (1523). It does not only contain descriptions of the hunting scenes of that time but also the characterisation of Grand Duke Vytautas and his hunting sprees: “Hunting that is ruinous to many men, / Sometimes it can be regarded as silly, / If such a high Ruler were not among them, / His name even today is worth highest respect. / The deep mind of unbending Vytautas who is famous for these inventions / strengthened the spirit of the warriors, forces of his Motherland.”

Literature: Žiliberas da Lanua, in: Kraštas ir žmonės, parengė Juozas Jurginis ir Algirdas Šidlauskas, p. 50, Vilnius, 1983, 1988.

Rimvydas Petrauskas