Friends and Friendship: Of Bees and Humans Living Together in the 15th and 16th Century

Is the life of bees similar to human friendship? Specialists have long been aware of the etymology of the Lithuanian word bičiulis (meaning a close friend) and have discussed it on various occasions, because the word refers to common features in the behaviour of bees and humans and has no analogues in other languages as far as its etymology is concerned. Entire theories have been offered that harmoniously interweave the being of pagan gods (such as Austėja, the goddess of bees) with that of humans (who share honey with bees) and of bees (who make honeycombs). But does this ethnographic poetry bear any historical reality?

Honey-laden friendship

The importance of beekeeping in pre-Christian Lithuania raises no doubt even though reliable sources on the matter are scarce. The essential role of beekeeping in the society of that time unfolds through the old peasant tradition of paying tribute in honey and through ritualised testimonies (pasėdžiai) of their servitude upon dukes and (or) their nobility that involved treating their owners with food and mead.

Pure honey and other bee products used to harmonise human relations by cooling off coercion and cupidity of the mighty.

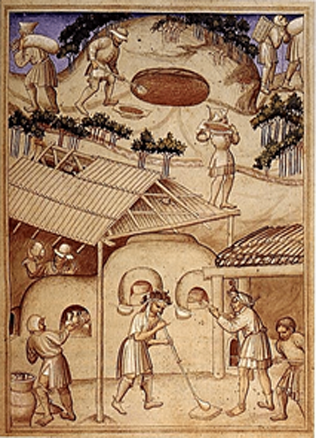

The importance of this kind of relationship started diminishing after the Christianisation. As peasants were turning into ploughmen, only a small group of peasant beekeepers (Lithuanian: bartininkai; Ruthenian: бортники or дровеники in the documents from Samogitia) continued paying tribute in honey, mostly collected from tree hollows. Usually these were the peasants living by vast forests. They worked their plots of land, just like the peasants representing other categories, but had to pay slightly lower tributes. Beekeeping of the time meant taking care of wild bees living in tree cavities. It was not before the second half of the 16th century that beehives began spreading slowly in Lithuania.

In most cases, bees lived in tree hollows and bred naturally, while the beekeepers would look after them by cleaning and repairing the cavities and taking some of their honey as a reward. The fact that beekeepers could only take about half of honey from each hollow (taking more would kill the bee colony) serves as an allegory for coexistence and friendship between bees and humans.

Another important feature of tending bees in natural hollows is related to the fact that even as late as in the 15th century the tradition was developing in the forests run by rural communities and almost uncontrolled by the state. Old customs, such as that of individual inheritance of the tree hollows with bees, regulated the number of bee colonies tended by each peasant community. Therefore, peasants had become the actual owners of most bee colonies long before the state or the owners administering their peasants (the nobility and the Church) seized the control over all forests.

No men or women, including the nobility, was allowed to destroy tree hollows with bees or take them over from any other person or obstruct the passage to the hollows, according to the Lithuanian legislation (the Statutes).

The ambiguous legal status of tree hollows with bees apparently was behind the tradition of giving some honey to the owner of the forest. This was how the beekeepers tried to ensure they could tend the bees freely. The custom is probably even older, because the beekeeper would “bribe” his neighbours by giving them presents at earlier times when forests belonged to the peasant community.

Beekeepers depended on the benevolence of their community and had to show their own goodwill in return. As the land control by the state and the nobility was growing tougher, the communal pressure on beekeepers was diminishing. Presumably, it was then that the tradition of cutting personal signs of a beekeeper into the trees with bee hollows was born. Landowners very often used these trees as landmarks of their own territories.

The echo of a forgotten communion

The conditions for natural beekeeping were changing rapidly in the 15th and 16th century, but some old customs survived. Historical sources from the late 16th century provide plenty of information about them. In the wake of the administrative reform (1564–1566), district courts were established and a large number of duplicates of property sale documents began accumulating in their offices. The papers, mostly in Ruthenian, sometimes refer to the Lithuanian custom of friendship through bees (бицюл, бицюловски, бицюловство, бицюлство) and beekeepers (битник, битниковство). Historian Konstantinas Jablonskis has carefully picked all of them from the sources and has systematised them. The custom must be very old, according to him, although the first indirect documented references emerge as late as in the 15th century. The relics of the tradition are still visible in Lithuania and Samogitia of the 15th and 16th century, just like in the territories inhabited by both Balts and Ruthenians. Ethnically mixed territories, such as districts of Grodno and Slanim, used a different term (сябровство пчол; literally bee friendship) to name the same phenomenon.

Friendship through bees implied a benevolent sharing of honey. This is why the documents often use appropriate paraphrases (пчолы на полы, миод на полы) meaning literally “bees in two” and “honey in two”.

The tradition of sharing honey between two beekeepers was often a sign of gratitude, because one of them would thank his counterpart for the bee colony he had earlier received from him as a present. Friendship through bees was common even between people of different estates in the 16th century, and nobles would often give half of their honey to peasants. The latter fact also indicates that the custom is old, its origins in the times when people saw no estate-related differences between them. The custom has changed over time. Already in the 16th century, the term “bees in two” meant an obligation for a peasant to give his owner half of the honey he collects from the trees growing in his owner’s land rather than a friendly tradition of honey sharing. The former duty is far from friendship through bees. We know that this kind of relationship was also present in Lithuania Minor, Sambia and in the lands of today’s Belarus. This is why we can guess that the true bičiulystė, or friendship through bees, existed only among the Balts. During the period of military expansion and growth of the Lithuanian state, the custom – though in the form of obligation – spread among some Ruthenian communities. In the 15th and 16th century, bičiulystė turned into a duty for any beekeeping peasant. Despite that, the term preserved its old meaning and essence in some regions of Lithuania in the 16th and 17th century.

After all, the friendship as the custom of sharing honey between two people correlates nicely with the tradition of commonly shared beer. Taking into account that the word beer could be used to name mead in the 14th century, it is likely that both customs were meant to emphasise and revitalise the communal solidarity. Humans, just like bees, lived in large families then.

Literature: K. Jablonskis, Lietuvių kalba viešajame gyvenime, To paties, Lietuvių kultūra ir jos veikėjai, Vilnius, 1973, p. 279–281.

Eugenijus Saviščevas