Feasts: the Splendour of the Public Consumption

Ghillebert de Lannoy, a knight and an envoy of the French ruler, visited Lithuania a couple of times and left several lines about the parties given by the Grand Duke Vytautas in 1421 in his memoirs. “After travelling through the lower Rus’, I arrived to the Grand Duke and King of Lithuania, Vytautas, whom I found in the Rus’ town of Kremenets together with his wife and one of Tatar dukes surrounded by many other dukes, duchesses and knights. […] The ruler rendered me great respect by treating me abundantly. He invited me to a dinner three times; he seated me by his throne where his wife and the Saracen Tatar duke sat too. By the way, I saw them eating meat and fish although it was Friday.”

The laconic story provides plenty of minute details characteristic to the parties of that time. The feasts take place in public, by calling in the people from the ruler’s environment or those deserving to be honoured by him. The ruler’s table is the centrepiece of the party with the ruler, his wife and honourable guests sitting around it. Most probably, all other participants also took their seats according to their rank in the ruler’s environment. Although the court of the Lithuanian ruler was already officially Christian, no one seemed to worry about adhering to religious restrictions concerning fasts. In the Middle Ages, any party in any European country involved loads of roasted meat, and altering old habits was not an easy and quick task to accomplish. That is probably why Lannoy never refers to the quality of food or the ways it was prepared. Obviously, dishes were not extravagant.

The abundance of food was most important rather than its preparation and look.

Historical sources say nothing about personal cutlery, hence it is probably too early to speak of any thought-out table serving.

A breakfast with the king

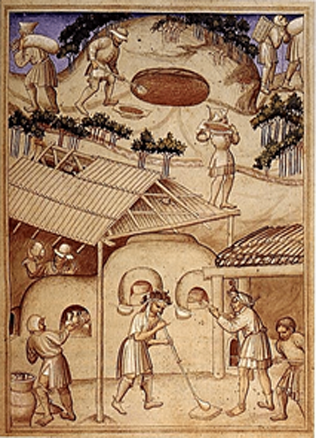

It was only in the 15th century that the traditions of feasting started to change in Europe. Professional cooks, books of food recipes and the norm of using personal cutlery spread over the whole continent from Northern Italy, the cradle of the Renaissance culture. As tableware was becoming more readily available, it turned into the object of pride for their owners who used their chances to demonstrate them, sometimes in curious ways, to a crowd of gawks. But even in the late 15th century, the court of the ruler of Lithuania and Poland remained largely at the sidelines of that trend.

Ambrogio Contarini, an envoy of Venice who was visiting the court of the Lithuanian ruler in Trakai in 1477, has left the following description of his breakfast with Casimir IV Jagiellon: “The next day, i. e. February 15th, the king ordered to give me purple damask clothes decorated with marten furs as a present. After putting them on, I was brought to the royal palace by a chariot pulled by six horses and escorted by four nobles and a group of others. […] After other speeches, I was taken into the palace where breakfast was ready. Soon the king came with his sons, following the trumpeters who entered bearing the royal glare. The king sat down first, then both of his sons to his right, while the first bishop of the kingdom took the seat to king’s left. I was offered a seat beside him, not far from the king. The nobility, who also took part in the celebration, took their seats further away. About 40 people were at the breakfast. As soon as new dishes were brought in, the trumpeters came forward and sounded their trumpets. Trays laid on tables, full of various food. The breakfast took about two hours.”

This episode, just like the one from the times of Vytautas’ reign, describes the same customs of feasting, the only difference being that they became better organised with time. Large numbers of guests attending the parties add solemnity to these events. Those people are not a crowd, because they observe the hierarchy of the court and take their particular seats at the tables. It looks like the number of guests attending parties was somewhat lower than that of servants, because the exclusive guests usually had escorting groups. The trumpeters brought a bit of rhythm into the two-hour event; waiters ran along the tables.

Food consumption resembles a splendid theatre performance in several acts when actors and spectators are the same people.

The pompousness of it all reflects the mediaeval spirit. Food is served on trays and people take it with their hands. What did they have to wipe them? The answer in not easy, because napkins became popular much later, in the Age of the Enlightenment. There are some hints in historical sources though referring to special servants, the towellers, in the early 16th century who would help the diners, or at least the ruler of Lithuania, to wipe (or perhaps to wash too) his hands.

Dining with a magnate: a performance at the table

It was not before the second half of the 16th century that the more or less important changes in the traditions of food cooking and consumption took place as far as the Lithuanian ruler, the aristocracy and even the nobility is concerned.

We can guess about that, because historical sources provide plenty of tiny hints, such as the mention of cups, spoons, and different table bowls made of silver, zinc and wood in estate inventories. They all refer to the triumph of personal cutlery and the emergence of extravagant dishes. Jerome Horsey, an Englishman who stayed at the palace of Krzysztof Radziwiłł, the voivode of Vilnius, in about 1590 is among the most renowned witnesses:

“His majesty invited me for a dinner and rendered me honour of being escorted by fifty halberdiers around the city and ordered horsemen and 500 armed guardians to accompany me to his palace. He himself, together with a group of young nobles, received me on a terrace and then took me into a large room where somebody played organ and sang. Voivodes, ladies and gentlemen, sat behind the long table, while he himself sat under a baldachin. I had my seat in front of him, right in the middle of the table. Trumpets sounded and drums beat. When the first dish arrived, jesters and poets started chatting lively, while instruments continued playing soft melodies. A group of splendidly dressed dwarfs, men and women, entered the room and filled it with harmonious and sorrowful sounds of their pipes and beautiful songs crowned with David’s tambourines and pleasant Aaron’s bells. I had to time to feel bored. His majesty drank to the health of Her Majesty the Queen of England. Bizarre figures of lions, unicorns, wingspread eagles, swans and other creatures were made of sugar, their stomachs filled with various wines and spices, and different sweets cut off them to savour, a silver fork with each of them. It would take long to mention all the different dishes and rare things. After a good treat, honoured and pleased, I was escorted to my room.”

The variations of the performances of public consumption were endless.

Literature: Kraštas ir žmonės. Lietuvos geografiniai ir etnografiniai aprašymai, parengė J. Jurginis, A. Šidlauskas, Vilnius, 1988, p. 52, 53, 55; N. Davies, Dievo žaislas: Lenkijos istorija, t.1, Vilnius, 1998, p. 250, 251

Eugenijus Saviščevas