Cerro Rico avalanche that turned the Nemunas Valley into the pond of Europe: the price revolution in Lithuania in the 16th century

The humanity dreaming of stability always aimed to conserve values. However, after a long-lasting period during when the values do not change, their reappraisal begins. It starts with hardly noticeable movement of small things – soaring prices, and eventually it turns into an avalanche that changes the lives of millions of people. In the past people rarely understood what was going on because sources of changes were beyond the horizon of their vision. Watching how things that seemed eternal were changing in their eyes, they perceived everything as God’s work forecasting the end of the world. The entire 16th century was like that when the most tremendous increase in prices was accompanies by the most intensive spiritual crisis in Europe – the Reformation.

Do You Know?

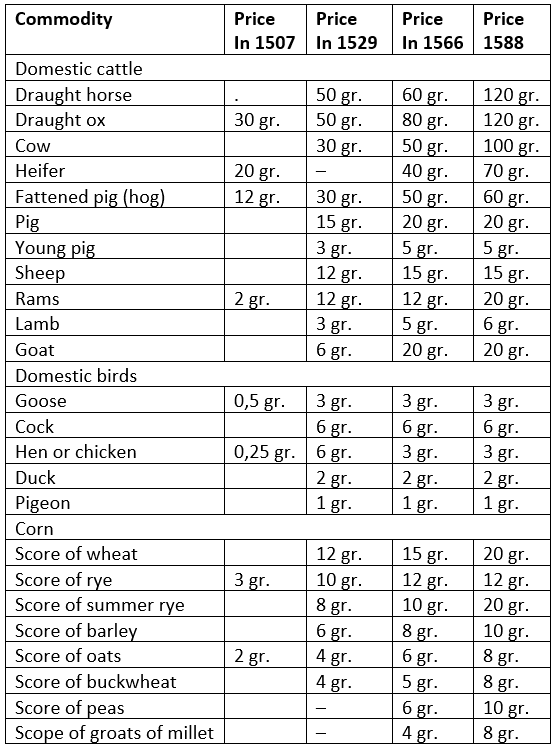

Price lists of three Statutes of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania represent an increase in prices in the 16th century: for example, large draught horned animals went in price more than twofold in Lithuania, cows – threefold, pigs – twofold, the price of sheep hardly changed, and goats went up in price less than twofold. Meantime compensation for the head of the nobleman killed dropped 3-4 times: after Europe discovered serfdom anew, the value of the free nobility that was difficult to be drawn into the market relations decreased.

The silver fever

After Lithuania’s baptism at the end of the 14th century, the country opened itself not only to the culture of Western Europe but also to its economy.

Catholicism gradually changed the mentality of the Lithuanians whereas trends of the economic development of Europe had an impact on their material life.

At the end of the 15th century the towns of the western frontier of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (especially Brest, Gardin, Kaunas, and Vilnius) took over the initiative of trade from the trade centres of old Rus’ in the south and the east (Kiev, Smolensk) that had been more active in the state until that time. Nature of trade changed: if in the 15th century settling accounts in kind prevailed in the international exchange and the system of duties (even merchants of Hansa were famous for this kind of trade), from the beginning of the 16th century the importance of settling accounts in silver coins rapidly increased. Using cash (monetisation) that was spreading in society was encouraged not so much by foreign trade as by the tax policy imposed by the State – transfer of some tithes of peasants into cash; the silver tax (one-time military duty) that became more frequent, therefore the development of monetary economy took place only in receiving precious metals through exchange with Europe.

European economy experienced a chronicle shortage of precious stones from the times of the Roman Empire at the beginning of the 16th century.

Though the scope of their extraction on the continent grew constantly (in the 14th – 15th centuries their large amounts were provided by Czech, Hungarian and Saxon mines), lots of them were used in trade with the Far East in exchange for luxury good (spices, textile products). Resources of precious metals of the New World unexpectedly put en end to this shortage when Potosi silver mine in Cerro Rico Mountain (currently Bolivia) was started to be exploited in 1546. At the end of the 16th century 30-40 tons of pure silver was brought to Spain through official channels every year from there (approximately the same amount was transported from the mine illegally). More mines operated in the New World. The wave of American silver swept through Europe causing a sudden activation of mining operations and at the same time increasing prices of many consumer goods. Throughout the 16th century they increased in price twofold or fourfold in Western Europe. That was the greatest price revolution until the middle of the 20th century.

Devaluation of money spread like infection in all countries, which traded with Western Europe more actively.

Inflation was individual in each of those countries.

Leaps in prices in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The 16th-century price revolution in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania has not been studied by the historian thus far. In the second part of the 15th century, with the population in the State increasing, towns growing and the network of towns expanding, wider consumption had to appear, which encouraged the use of money and a periodical change in prices. From the beginning of the 16th century work of Lithuanian mints became more regular and local coins ousted the foreign ones from the market. Though Potosi silver could reach Lithuania, it seems that the largest part of the coins minted there was from Polish silver of lower quality. Hence, Potosi avalanche seems to have had an indirect impact on the Lithuanian market: it only slowed down the flow of silver of Eastern Europe of lower quality from the region.

There are almost no sources consistently reflecting the prices in Lithuania in the 16th century therefore perhaps the best systematic source is three Lithuanian Statutes.

On the one hand, the mere fact that pricelists were included in legal codes shows the medieval belief in stable prices.

On the other hand, when comparing price lists in all three Statutes, which came into effect in 1529, 1566, 1588, we see that the prices of the same commodities were unstable. Prices fixed by the 1507 decision of the ruler were presented at the prices entered in the Statutes for comparison. The latter, as compared with the market prices, were reduced therefore they should not be given any prominence.

Prices according to three Lithuanian Statutes

Non-threshed corn is counted in scores – 60 feet in each. About half a barrel of dry substance was received from them – about 100 l

Throughout the 16th century (assessing on the basis of the price-lists presented in the Statutes) large draught horned-animals in Lithuania increased in price more than twofold, cows – threefold, pigs – twofold, the price of sheep hardly changed, goats went up in price a little less than twofold; the prices of poultry remained stable, corn increased in price almost twice.

Devaluation of “the nobleman’s head”

The price of the measure of all values – the individual – also changed. In the presence of a sudden increase in monetary economy the Europeans found serfdom again: serfs from Africa were transported to the plantations and mines in America more and more often.

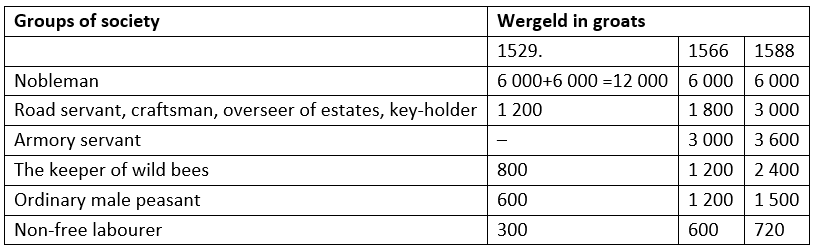

In Lithuania, leaps in the price of man can be observed when comparing the amounts of compensations (Germ. Wergeld, or money per head) presented in three Lithuanian Statutes for murder of a representative of different groups of society.

All three Lithuanian Statutes state that 100 shocks of groats (6 000 groats) was paid for a noblemen’s head to the family of the killed. But alongside this payment the First Statute provided for the payment of the same amount to the Ruler. Hence, in the first half of the 16th century a nobleman’s head cost a huge amount of 12 000 grosz. The Wergeld in the Second and the Third Statutes paid to the family of the killed person remained the same (100 shocks of groats) but the payment to the ruler disappeared. Therefore the Wergeld of a nobleman fell in price almost twice, and taking into consideration the fact that the standard of living of the majority of the population increased, a real price of a nobleman’s head fell in price 3-4 times in the second half of the 16th century.

Hence, the amounts of court compensations show that with the values of exploited labour increasing, the value of the free nobility who were difficult to be drawn into the market relations fell. Perhaps the nobility suffered mortification experiencing these changes, but they were not in danger of meeting the fate of the peasants – the possibility to be sold to another owner like animals.

Eugenijus Saviščevas