Byzantine Painting in Gothic Churches: a Cultural Dialogue Determined by Politics

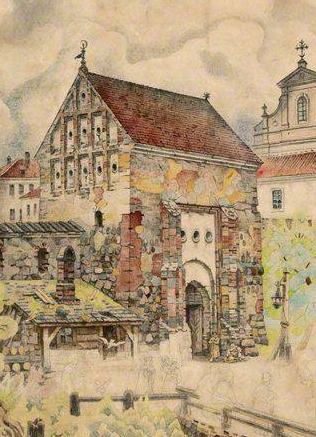

There is scarce surviving data about the early art in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. It is believed that both altar pictures and sculptures were to be installed in the churches, built in the country which had just adopted Christianity. Regrettably, only few of them have survived. The first sacral buildings, usually built of timber, have also been doomed to perdition. In the course of centuries, the castles built of brick fell into decay and turned into ruins. Several early monuments made of brick were rebuilt. In them, the remains of the first layers of wall painting are hidden under the layers of coating applied at a later time in history. Fortunately, such priceless remains are occasionally uncovered by restorers.

The treasures hidden under the layers of plaster

In 1985, the fresco of a crucifix, dated back to the 14th century, was discovered in one of the crypts of the Cathedral Basilica of St. Stanislaus and St. Ladislaus of Vilnius. In 2006, fragments of painting dated to the beginning of the 15th century, were found in the Trakai parish church. The researchers’ assumptions that some of the indoor walls of the Trakai Island Castle were decorated with painting were based on the stylized copies drawn in the 19th century by the painter Vincent Smakauskas and on several drawings and photographs dated to the end of the 19th century. Unfortunately, these valuable artefacts have not survived up to our days. In the aforementioned examples, the following specific trend can be identified: in the end of the 14th-beginning of the 15th centuries, the walls of the Gothic brick buildings in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania were adorned with paintings as a common Byzantine technique used for monumental decoration. The extent of this tradition has not yet been stated; there is no answer so far to the question whether it prevailed only in ducal courts, or whether it covered a wider scope. Furthermore, there is no single answer as to why the architecture of the period in question was created following the western architectural example (possibly by the architects invited from abroad), whereas their interior decoration was entrusted to the artisans, the artistic expression of whom had been formed in the Orthodox cultural environment. Similar trends of intermixture of styles can also be observed in other European countries, situated in the periphery influenced by both the Western and Eastern Churches or the countries which are known to have maintained close ties with the empire of Byzantium (e.g., Venice). However, in all the respective countries such trends were predetermined by specific factors.

Decor according to the King’s taste

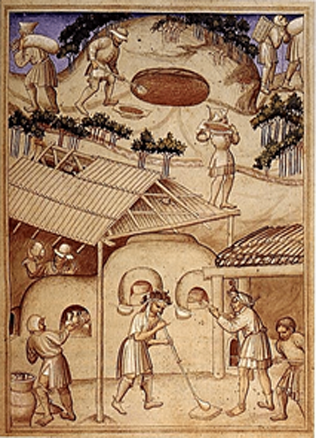

Several analogous cases are known in Poland, when the patterns of the Byzantine wall painting were discovered on the walls of a Gothic chapel or church. All of them are related to the name of Władysław III Jagiełło. Painters from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania are believed to have been invited by the Ruler to paint the walls in Byzantine tradition, working on a commission by the King of Poland. In these cases, it would be appropriate to talk about the first ever historically known export of artistic culture of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania beyond the national borders of the state. Jan Długosz was the first to claim that Jagiełło valued the Byzantine tradition of art far more than the Western tradition, therefore he gave orders to decorate his bedroom in Wawel Castle, Krakow, and several important Catholic churches, such as the Gniezno and Wawel Cathedrals, Sandomierz and Vislica Collegiates as well as the Benedictine St. Cross Church, in the Greek-style painting (more graecorum).

St. Trinity Chapel of the Lublin Castle, famous for the numerous frescoes, painted under the supervision of the artisan Andrziej in 1415–1418, is the best-preserved illustration of all the foundations by King Jagiełło.

The painting decorates the vaults of the chapel and the upper wall panelling; its style combines both Byzantine painting and Gothic elements. This chapel helps us to better visualize the overall picture, how other similar churches of that time could have looked like. On the walls of this sanctuary, images of divine characters are painted, scenes of Christ’s passion are portrayed and the scenes showing twelve celebrations, observed during the liturgical year of the Eastern Church are depicted (Revelation of the Holy Virgin Mary, Jesus’ birth, Jesus’ Sacrifice in the Temple, Jesus’ baptism, the Resurrection of Lazarus, Triumphal Entry into Jerusalem, Crucifixion, the Descent into Hell, the Ascension, and others) are depicted. On the lower part of the walls, Fathers of the Church, Saint Hermits and Martyrs are portrayed. The scenes from the Holy Scriptures and hagiographic stories are reinforced with complementary images, related to Jagiełło’s character, such as his heraldic symbol and personal images. In one of the frescoes, Jogaila is portrayed kneeling in front of the Mother of God, sitting on the throne with Child, at her side, his celestial guardians, St. Nicholas and St. Constantine the Great, are depicted. One of the most significant scenes is the portrait of Jogaila, showing the Ruler on horseback; the angel floating above puts a crown on the Ruler with one hand, and hand in the cross with the other. Such artistic composition has been devised to convey a symbolic concept of the Christian Ruler as Defender of God’s anointed faith.

Historic implications of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in Byzantine Art

Within the territory of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the most famous surviving wall paintings were created in Trakai, namely in the Trakai Castle and the parish church. The research conducted by the art historian Giedrė Mickūnaitė has revealed that the wall paintings discovered in the Church of the Visitation of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Trakai had been commissioned by the Grand Duke Vytautas in the first half of the 15th century (probably up to 1419). At the end of the church, on the northern, partially on the western and possibly on the southern wall, the composition of the Last Judgement was painted. The other parts of the church might have also been painted; however, there is no specific data about the scenes of such painting.

Further historical research might be helpful in shedding light on how and to what extent the aforementioned foundations by Vytautas and Jagiełło could have been related to the efforts, aimed at implementing the union of the Catholic and Orthodox churches in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Timewise, both the frescoes discovered in St. Trinity Chapel of Lublin and the decoration of the Trakai church coincided with the major events in an attempt to consolidate this union, the idea of which was particularly supported by Vytautas. Metropolitan Gregory Camblak, residing in Navahrudak announced in 1415 the independence of the Orthodox Church of the Kiev Metropolitan of Moscow and the Patriarch of Constantinople. In 1418, he was sent to the meeting of Constance, during which in the presence of Pope Martin V he expressed support for the idea of the union in question.

The Catholic churches of the 14th-15th centuries also boasted icons, which significantly affected a further tradition of sacral painting in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (modified features of the iconic painting can be observed in sacral Catholic painting of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania as late as in the 17th century). The studies carried out by art historians enabled the identification of the icons which had been commissioned by Jogaila and created by the artists working in Lublin and Sandomierz as well as the icons surviving in the Ukrainian Orthodox churches.

The tradition of painting icons was particularly respected and cherished in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Part of the icons were imported. The message recorded in the legends of the pictures of Our Lady of Trakai (both the Old and the New Trakai) about the icons donated to Vytautas the Great by the Byzantine Emperor is believed to have had an authentic historical basis. This does not invalidate, though, the existence of local schools of icon painting. This is testified by the surviving old images of Our Lady, e.g., the so-called Volyn icon of Our Lady in the Orthodox church of Lutsk, funded by Vytautas the Great.

Literature: Mickūnaitė Giedrė, Trakų parapinės bažnyčios restauravimas: atradimai, praradimai, vertinimai, in: Atrasti Vilnių. Skiriama Vlado Drėmos 100-mečiui, sud. Giedrė Jankevičiūtė, Vilnius: VDA leidykla, 2010, 242–251.

Rūta Janonienė